After hiking a few thousand feet up a slope or taking a lift at a ski area, you open your water bottle and hear a momentary rush of air. Or after staying at a high-altitude resort and returning home, your shampoo container is partially crushed.

On higher peaks we have less energy and move a bit slower. Go even higher and altitude sickness strikes. Water boils at lower temperatures at high elevations, causing cooking times to lengthen. Why? All these are due to decreased air pressure. The effects are often quite noticeable.

Atmospheric pressure decreases with elevation for a good reason: It's dependent on the weight of the air above you. If you move higher, there is less air above you and thus pressure declines.

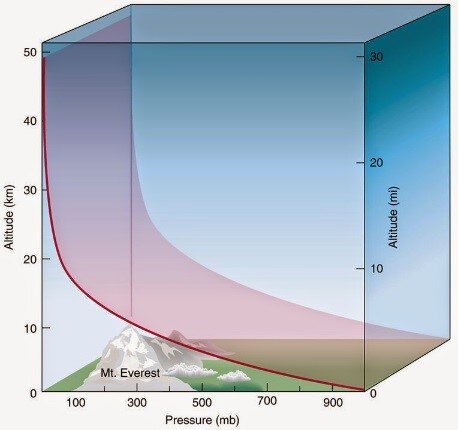

Interestingly, pressure decreases with height at different rates, depending on your elevation. Pressure falls more rapidly near the surface where the air is dense and less rapidly aloft where the air is thinner (see figure).

Let's explore how pressure declines with elevation.

At sea level, the average air pressure is about 1013 hPa (hectopascal). Also known as a millibar (mb), hPa is a unit of pressure. By roughly 5,000 feet in elevation, the pressure has declined about 15% to approximately 850 hPa.

Ascend to about 10,000 feet and the pressure drops to roughly 700 hPa, with 30% less air pressure and oxygen. No wonder such elevations sap our strength and sometimes lead to headaches and dizziness.

Reach 18,000 feet above sea level and pressure drops to about 500 hPa, roughly half the pressure measured at sea level. Few of us can function at this altitude, which is close to the elevation of the highest permanent human settlements.

Curious about air pressure as you climb or hike? Carry or wear an altimeter, which is essentially a small barometer. An altimeter makes use of the normal change of pressure with height and should be calibrated with a known elevation at the start of a hike. Since the actual change in pressure will typically be slightly different, altimeters often possess small errors (generally no more than 25-50 feet) over a hike of a few thousand feet in the vertical. Interestingly, pressure altimeters often provide more accurate elevations than GPS units, which frequently are off by 50-100 feet and are sometimes inoperable under dense tree cover.

Or, simply use your phone. Many smartphones now have pressure sensors and there are a number of altimeter apps available at little or no cost. Climb on.