Welcome to the world of watersports. Whether it's your first time paddling or you're a seasoned water guide, there's always something to learn about the splashiest element. Your water adventures should include a sound knowledge of the environment you choose to recreate in, whether it's a lake, a river or along the coast. So, before you jump in, you'll want to get familiar with reading water gauges, understanding tides and currents and planning your safety equipment.

We cover the key concepts so that, while you're out on an aqua-based trip, you can spend more time enjoying and less time wondering.

Read on, or click on the links below to take you directly to a topic of interest:

- Tides vs. Currents: Check out the difference between tidal rise and fall of sea levels and one-directional movement of water, called currents.

- Lake Dynamics: Wind is a major factor in a lake's currents, although some lakes can experience tidal fluctuation as well.

- River Dynamics: Learning how to read a river will help you navigate hazards and use currents and hydraulics to your advantage.

- How to Read a USGS Water Gage: Learn how to navigate the current and historical data presented by the United States Geological Survey's water gauges, located on 11,000 waterways around the country.

- Water Safety Gear: What to wear on the water, from lake days to whitewater paddling.

- Water Rescue: Know the three types of water rescues for when your paddle goes awry: self-rescue, professional rescue and buddy rescue.

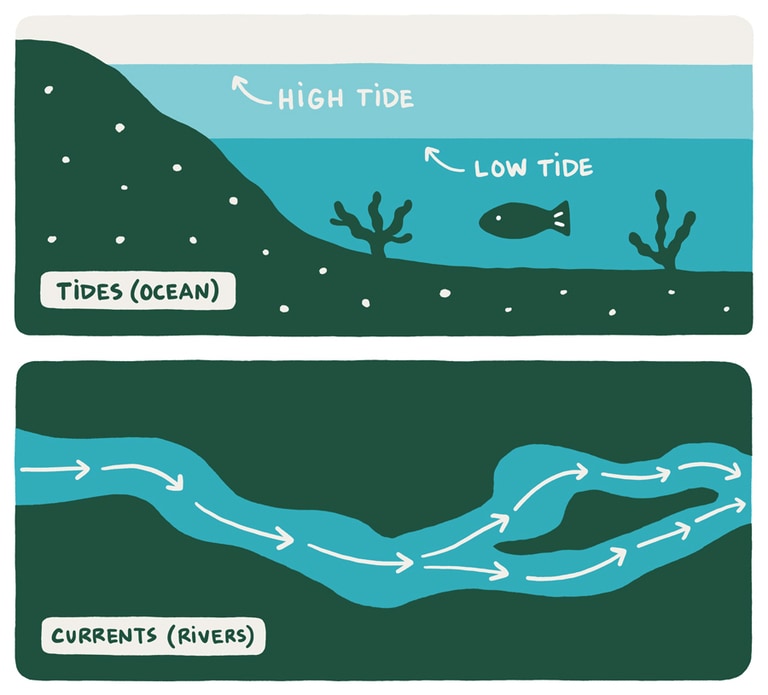

Tides vs. Currents

Understanding how water works will help you navigate more easily, and safely, whether you're in a vessel, on a board or swimming.

- Tides: The daily rise and fall in surface water levels of oceans—revealing and disappearing stretches of beach, for example—and can vary drastically from day to day, or in different locations. Tide tables are key for understanding when sea levels will rise or fall along the coast.

- Currents: A mass movement of water in one direction, such as in rivers—although currents exist in the ocean as well. The strength of currents in a river can be gauged by water levels and flow rates.

Ocean currents can be affected by tide levels, surface winds and even temperature of seawater (or incoming water sources). Both tides and currents can pose hazards for your adventure or, if you know how to work with them, aid you in your journey. For instance, a low tide could allow you to portage around a windy area, while a high tide could reduce the risk of sharp rocks or sandbars stopping your boat as you cross a channel.

Using currents in rivers, lakes and the ocean can help you steer and conserve your strength by utilizing the natural "driveshaft" of the water. With rivers, the faster current helps you use less muscle to keep your craft moving downstream, and can even set you up for your next move around a rapid or hazard in the water. Alternatively, slower currents (or eddies) may help you wait for other boating partners or situate yourself for a rescue before continuing downriver, without fighting up current to stay in place.

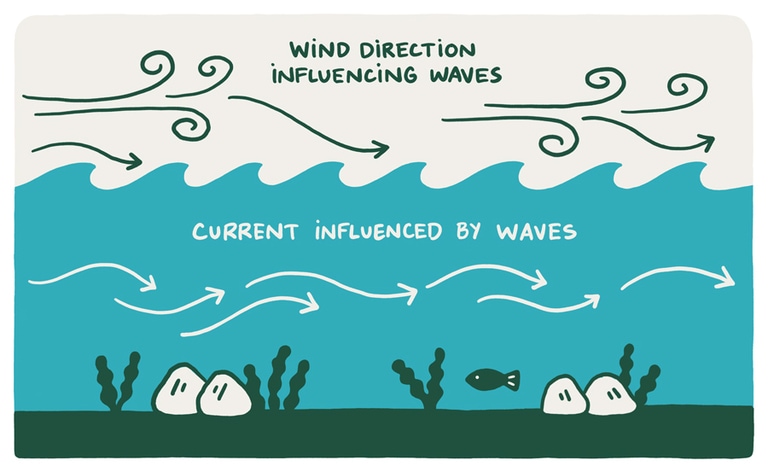

Lake Dynamics

The biggest factor to contend with on lakes is the wind. While lakes don't generally have tides (except for the Great Lakes, which do have tidal fluctuations twice a day), wind determines the direction of waves, which can contribute to currents beneath the water's surface. It can also make your direction of travel easier (with the wind to your back) or more difficult (paddling into the wind).

- Choosing Watercraft: The type of watercraft you use may determine your ease of navigation on a windy (or calm) lake. A rowboat may serve you better on a windy day, with the ability to capture progress more easily with two oars. The lower profile you have, and the heavier the vessel, the easier it should be to navigate in wind. However, light watercraft, like stand up paddleboards (SUPs) or sit-on-top kayaks, have the advantage of being easily maneuvered, so if you're a strong paddler you may be able to work your way across the lake without the wind stealing your momentum.

- People Power: Two paddlers in a canoe can also work in unison to beat the wind and steer around a blustery lake. If you're working with the wind at your back, simply place your paddle in the water (in case you need to steer) and let the waves and currents take you.

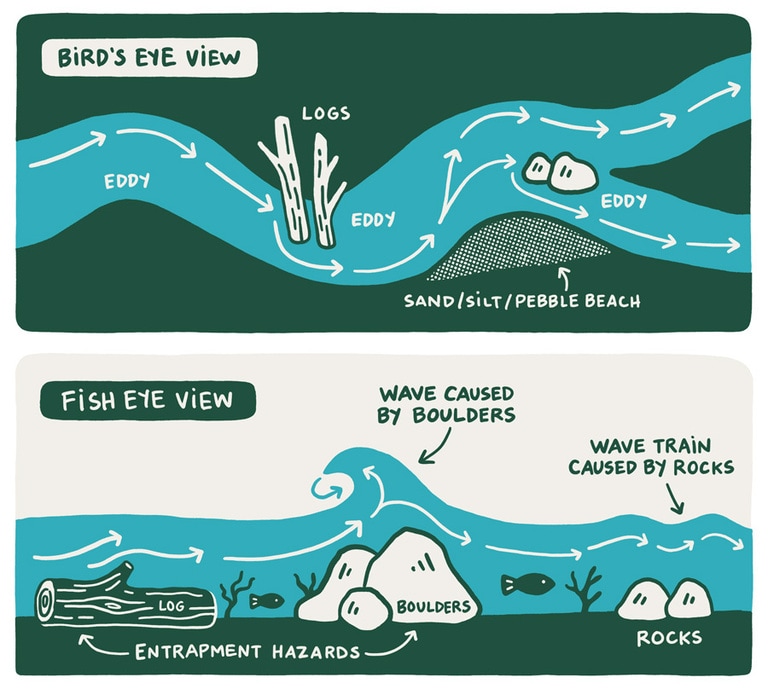

River Dynamics

When you know how to read the river's hydraulics and use river currents to your advantage, the amount of effort you exert while paddling or rowing decreases dramatically. "Reading rivers" is a skill, just like reading a tide table, but is enormously handy to those who learn it. Here are the two primary elements you'll want to understand:

- Current: A swift current area in a river that can move in any number of directions. The current gives itself away with help from bubbles, branches or leaves that show us how quickly the surface of the water is moving. Currents can also "bounce" over shallow areas of water as a giveaway, so vessels don't get stuck.

- Eddy: A current area behind a rock, log or other obstruction. An eddy can look like a still area of water or can be recirculating, where the water moves upstream again, counter to the direction of the main current.

River dynamics can include hazards like dams and logs, shallow water, entrapments on the bottom of river from rocks, wood or scrap metal and more. These hazards often create one of two dynamics: rapids or strainers.

- Rapids: These are formed from water moving around, over or even under items in the water. As illustrated above, rapids can produce "wave trains" of small to medium waves down one section of river, recirculating waves or even holes (big drops of water, usually combined with recirculating water, that can act like a washing machine for boats and swimmers). According to the International Scale of River Difficulty, there are six standard ratings for rapids. Class I is the easiest rating, while Class VI is considered "unrunnable." (Some rivers, like the Colorado River segment through the Grand Canyon, however, use a Class 1-10 rating system.)

Standard ratings for rapids

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| I (Easiest) | Steady moving small waves, if any, and few hazards. Think of this as a low-risk, lazy river. |

| II | Small, straightforward rapids that are easily run without previously scouting. You may need to maneuver a little to avoid a rock or a splashy wave, but consequences are lower. |

| III | Rapids with medium and/or irregular waves that include strong eddies and currents. Competent boat control is required, with challenging boat maneuvering possible. While major hazards can be easily avoided, scouting the rapid ahead of time may be necessary for less-experienced boaters. |

| IV | Powerful rapids with large waves and holes, or narrow passageways with tight maneuvers needed. Precise and experienced boat handling are necessry for safe passage. Scouting can be required, as some rapids may call for particular moves to power through strong waves or avoid hazards. Self-rescue is difficult, so make sure you have a safety team either in another boat or on shore, just in case. |

| V (Most Dificult) | Turbulent, long or obstructed rapids that pose a high risk. There will be unavoidable, large waves and holes or chutes with debris. Eddies may be extremely difficult to find or catch. These rapids should only be run by very experienced boaters with rescue training, good fitness and proper equipment, as rescues can be very difficult and swimming can be hazardous. |

| VI (Unrunnable) | Only extreme athletes will attempt this class of rapid, as it usually involves a significant height, extreme volume of water and high turbulence. We call it unrunnable for a reason! |

- Strainers: Piled debris that allows water to "strain" through, but is easy to get trapped against as a swimmer. Strainers could be a single wide log blocking a channel to a beaver dam or debris to a tangled net across a current.

How you approach different rivers' dynamics depends on a variety of factors, including, above all, what type of boat you plan to use. How you navigate a raft through a Class III rapid may be very different than how you navigate a whitewater kayak through that same rapid. Take safety courses organized by outdoor organizations or an REI Co-op in your area; practice with your intended boat in easier water—and with experienced boaters—before trying larger rapids or longer stretches of river.

Other factors that can affect the river's dynamics include increased rainfall or snowmelt, dam releases, drought, rockslides, fallen trees creating strainers and man-made hazards like a bridge collapse or fill dumped into the water. Always check the recent weather forecast and river gauges for the stretch that you intend to boat on, and scout as much as possible, both from your boat or by eddying and walking downstream before you paddle on.

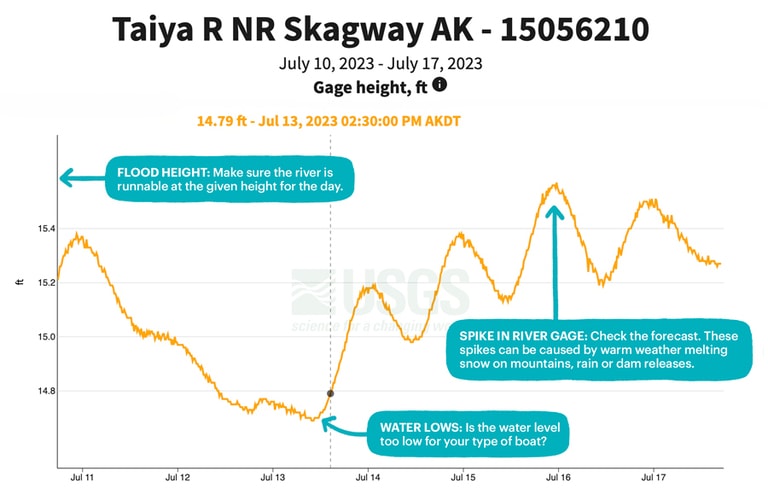

How to Read a USGS Water Gage

Boaters have access to the United States Geological Survey, which measures and records the water flows for nearly 11,000 rivers, streams and creeks. These water gauges (the USGS spells it "gage") give us an excellent look into three key variables:

- How high water levels are. How high a body of water has risen or fallen. Much like tides in the ocean, rivers and lakes can rise and fall. These changes aren't as affected by the moon, but instead spike upward with snowmelt at higher elevations, rainstorms or planned dam releases. In the example used in the chart above, the Taiya River in Alaska is considered in flood stage and should not be rafted if the water has risen over 16 feet at gauge. This doesn't mean that the entire river is only 16 feet deep, just that this very specific point measures at 16 feet high; other areas may measure higher or lower. However, that much of a rise means that the river has flooded out and may pose more hazards from strainers and debris.

- How many cubic feet per second (cfs) the river is running. This measurement uses the following formula to signify how much water is moving downriver at what rate of speed: river width × depth × speed (flow and gradient) = cubic feet per second (cfs). Each cfs unit is equal to about the size of a basketball, so if a river is flowing at 4,000 cfs, that's like 4,000 basketballs going past you in one second. That's a lot of water! Certain riverways are only passable at higher or lower cubic feet per second, and can change upgrade or downgrade a class of rapid with a cfs change—so make sure to check guidebooks or with knowledgeable local boaters to ensure you're planning to go out at an appropriate time.

- Whether the above numbers are historically accurate (or an anomaly). If the section you intend to boat has historically been at 3,000 to 4,000 cfs every May, but snowmelt caused it to run at 7,000 cfs this May, consider boating a different section, as these higher numbers could make the river experience totally different.

Water Safety Gear

Dress for your entire environment. While it may be sunny and warm above the waves, most water environments are significantly colder, which is why we love them on hot summer days. Rivers with snowmelt or glacial water can hover just above freezing temperatures by the time they reach your put-in; seawater averages 70°F in summer in New England, which would still be considered a very cold shower.

Hypothermia is one of the biggest dangers with water emergencies, along with drowning—the clothing and equipment you carry could make or break your experience on the water.

1. Water Clothing

For almost every water environment, quick-drying materials make for the best layers. Avoid cotton, as it absorbs water and takes longer to dry, which can be heavy and cool you down quickly when you don't want it to. If you're headed for lots of rain or a whitewater environment, waterproof materials like splash pants, a splash top (or rain jacket), or waterproof shoes can be extremely helpful at keeping you warm and dry. If your environment is warm but you may be in cold water, try neoprene (e.g. wetsuit) materials under shorts or swim trunks. Most of all, stick with closed-toed shoes. Sandals are fun, but cutting up your toes on shore or on logs and rocks under the water isn't.

2. PFD or Lifejacket

Arguably the most important piece of equipment on the water is your personal flotation device, (PFD) or life jacket (also known as life vests or life preservers).

Life jacket: As the name suggests, life jackets are designed to save your life. A life jacket's aim is to keep the swimmer's head above water, whether they're conscious or not. These flotation devices require a different rating than a PFD and generally have a thick head cushion to keep you afloat and will self-right you onto your back, protecting your airway from the water. These are generally what you'd wear on a slow canoe trip or a motorized boat.

PFD: Designed to keep you afloat, but not necessarily to save your life if you're unconscious. They are designed with more freedom for activity in mind, rather than lifejackets, which are meant for lower-effort watersports. These flotation devices are rated to provide extra buoyancy to lift a swimmer to the water's surface, but lack the head support of a lifejacket.

Read more: How to Choose PFDs (Life Jackets)

3. Rescue Knife

A rescue knife is a necessity in emergency situations. More often than not, you'll use it to make lunch; however, a knife is paramount to staying safe from entanglement hazards like fishing line or poorly placed throw lines. Most lifejackets and whitewater PFDs have a lash tab to attach a knife to the front or shoulder, but if you have a small pocket knife on hand already, zip it into one of your PFD's pockets.

4. Whistle

A whistle is a great means of communication in an otherwise noisy environment. Pick a whistle in a bright color so you can spot it more easily during an emergency. Attach it securely to either the shoulder of your PFD or inside a zipped pocket, but make sure the lead is still long enough to reach your mouth. I prefer to attach mine to my shoulder strap with a thick hair tie—this way, it stretches to my mouth but stays tight to my shoulder to avoid catching on limbs, oars or paddles when I don't need it.

5. Carabiners

Only use locking carabiners for your emergency rescue gear, as non-locking carabiners can catch and attach to ropes and objects that you might not want to be attached to in an emergency. There are also toothless carabiners, thatwhich are even easier to unclip from ropes in your boat!. Carabiners are used for rescue ropes systems (like a Z-drag), but can also come in handy when attaching your gear to your boats.

6. Throw Bag

For whitewater boating, a throw bag is your literal lifeline. Throw bags are low-profile and easy to toss to someone in need of rescue the water. If you're being rescued, hold the bag (not the rope) against your chest and float on your back so your face remains above water and your rescuer can pull you toward the boat more easily.

7. Waterproof Medical Kit

Have a medical kit stocked with appropriate levels of equipment, depending on how far you are from emergency rescue help or how long you plan to be gone that day. You can build your own kit and house it in a dry bag, or purchase one designed for the water. No matter what you decide, be sure to always bring the basics with you on your water adventures.

Water Rescue

There are three types of water rescue:

- Self-rescue involves the ability to "swim smart": staying away from ocean currents, using river currents to bring you to land, and swimming with your feet downstream to intercept hazards and push away from them. It also includes pulling yourself up and over a strainer or back into your own boat using the edges of your boat or the assistance of a "flip line" in whitewater circumstances. The more you know how to maneuver yourself to safety and back into your own boat, the better off you will be in dicey situations. Read more: How to Do a Kayak Self Rescue.

- Professional rescuers like the Coast Guard or fire department are specifically trained to respond to water emergencies. Still, knowing how to quickly rescue yourself—or your friend—could make the difference if your adventure takes an unexpected turn.

- Buddy rescue skills include using a throw bag effectively or pulling someone back into a boat by their life jacket (watch this video for instructions). Setting yourself up in a safe spot is paramount before you help a "swimmer," otherwise you could become the one who needs rescuing. Read more: How to Do a Kayak T-Rescue.