Since President Trump took office in 2017, his administration has rescinded or proposed to rescind dozens of policies rooted in environmental protection, often in the name of economic growth. The rollbacks come as scientists warn of a climate emergency that requires swift, coordinated global action through stricter regulations meant to control emissions.

Nearly 100 environmental policies have been repealed—or are in the process of being repealed—since Trump took the helm, according to The New York Times. Proponents of the measures say the rollbacks will help advance the economy and streamline regulations the administration claims are burdensome to industry.

But others fear the relaxed regulations—many of which are meant to curb pollution and protect natural resources—could accelerate climate change, worsening an already dire situation. Global greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 1.5 percent each year over the last decade, according to the 2019 Emissions Gap Report. The world’s 20 richest countries, including the U.S., are responsible for 78 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions. To keep the global temperature this century at 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels (a temperature deemed safe by a U.N.-supported panel of scientists), emissions would have to decline by 7.6 percent each year over the next decade. The stark reality has motivated millions around the world to speak up and demand climate-conscious policy.

With numerous environmental rollbacks, it can be overwhelming to track each one. To make things easier, we’ve broken down six policy proposals that are particularly relevant to recreationists and public lands advocates. Click through the article to learn more about each one.

Revising NEPA

The Trump administration in January 2020 proposed major revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act, which since 1970 has outlined an environmental review process for federal projects like pipelines and highways. The administration’s stated goal is to aid economic expansion by speeding up and streamlining environmental evaluation.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: National Environmental Policy Act

- Agency: Council on Environmental Quality

- Why it matters: The proposed standards could alter review periods and limit the public’s ability to comment on major infrastructure projects that affect the environment

- Status: Proposal

- Next step: The administration is accepting comments on the proposed changes through March 10.

LEARN MORE

Proposed revisions to a landmark environmental law could severely limit the public’s ability to provide input on major infrastructure projects that affect the environment, including public lands.

The Trump administration in early January proposed major revisions to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which since 1970 has outlined an environmental review process for federal projects like pipelines and highways. The goal, as with many of the administration’s proposed regulatory changes, is to aid economic expansion—in this case, by speeding up and streamlining environmental evaluation.

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)—the federal agency that enforces NEPA—proposed the revisions, which could alter everything from the public’s ability to comment on proposed projects to the ways in which agencies review environmental impact.

“America’s most critical infrastructure projects have been tied up and bogged down by an outrageously slow and burdensome federal approval process,” President Trump said Jan. 9, adding that the process wastes money, stalls projects and denies people jobs.

President Nixon signed NEPA—often considered the “Magna Carta of federal environmental laws”—as one of the first national policies for the environment. The administration created it in response to threats to clean air and water, said Brad Brooks, acting senior director of agency policy and planning at The Wilderness Society.

“It protects the things we need as a human species to survive, period,” he said. NEPA is different from other environmental laws because it has such a wide reach: It applies to most federal agencies across the political spectrum. Revisions will impact projects, permits and land management changes overseen by those agencies.

Adam Cramer, founding executive director of the Outdoor Alliance, said the revisions will significantly impact recreationists because—like for everyone else—it will become more difficult for them to comment on proposed projects that affect public places like trails, forests and parks.

“Given how much outdoor recreation takes place on public lands … this isn’t an abstraction for people who care about the outdoors,” Cramer said.

Under the proposed changes, people would have to provide comments that are far more detailed than what is mandated under the current law. For instance, an agency could disregard a comment if it voices a general concern not supported by data and methodologies, Brooks said. To have it considered, the individual would have to provide information about the environmental, economic and employment impacts.

CEQ spokesperson Daniel Schneider said in email to the Co-op Journal that the changes are meant to “promote meaningful public comment.” He said federal agencies will be encouraged to solicit public input earlier in the process and use new technologies like social media to make evaluating proposals more efficient.

But Brooks said the changes would still make commenting tougher for the average person who doesn’t have a law or science background, largely due to the amount of information they’d have to provide to support their comment. “The way (NEPA) is right now … you don’t have to be a lawyer to participate in the process,” he said.

The revisions also could result in fewer comment periods overall. CEQ is proposing that agencies conduct fewer environmental impact statements (EIS) in favor of more environmental assessments. The latter—typically reserved for projects where it’s unclear whether there will be a major environmental impact—requires a 30-day comment period compared to the 60 to 90 days mandated for an EIS. An EIS is required for large projects, such as a major energy plant or pipeline, where an environmental impact is certain.

“The new rules would dramatically reduce the number of projects that have a comment period, and if they do have a comment period, the agencies now have the discretion to truncate that period,” Brooks said.

Additionally, the revisions could allow agencies to impose a bond on an individual or organization if an agency has to delay a project in order to consider its environmental impact. “Think about the people who have the financial means to post a bond for some of these big projects,” Brooks said. “Who can afford to do that?”

Agencies within the Department of Interior who stand to benefit from the revisions support the changes.

“The purpose of NEPA is noble; its application, however, has gone off the rails,” David Bernhardt, Department of Interior secretary, said in a January news release. “The action by the (CEQ) is the first step in bringing common sense to a process that has needlessly paralyzed decision-making.”

The Bureau of Land Management, which is an agency within Interior, and the Department of Transportation, declined to provide a comment specific to their agency.

The revisions will place new limits on EIS’s. The existing law requires agencies to hire a third party to assess potential impact to the environment, but the revisions could make it possible for an agency to do its own assessment, creating a conflict of interest.

The administration also proposes that the assessments be capped at no more than 75 pages and take no longer than two years to create. On average across all federal agencies, these statements are about 600 pages and take about 4.5 years to create. However, less than 1 percent of projects each year require this level of assessment.

Cramer said the revisions short-circuit the public’s ability to engage with federal projects. Though it’s likely there will be litigation, Cramer said the best thing people can do right now is comment on the proposed NEPA revisions. They have until March 10.

Photo Credit: Will Porada

Paris Climate Accord

On Nov. 4, the Trump administration provided notice to the U.N. that the U.S. would be withdrawing from the Paris climate accord. The withdrawal will take effect on Nov. 4, 2020.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: Paris climate accord

- Agency: Executive branch

- Why it matters: It aims to hold nations accountable for meeting targets that help combat global warming.

- Status: The Trump administration began the withdrawal process on Nov. 4, 2019.

- Next step: The withdrawal is set to take effect on Nov. 4, 2020.

LEARN MORE

In response to a rapidly warming planet, nearly 200 countries have signed the 2015 Paris climate agreement, each pledging to play a part in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. The primary objective is to limit this century’s global temperature increase to at least 2 degrees Celsius, while attempting to hit a more ambitious goal of capping the increase at 1.5 degrees Celsius.

But in November 2019, the U.S. began the process of withdrawing from the accord. President Trump first announced his intent to leave the agreement in September 2017, saying the treaty placed unfair environmental standards on American businesses and workers, according to The New York Times. The Trump administration initiated the action on Nov. 4—the earliest it could do so—though the withdrawal won’t take effect for a year.

The move undercuts the international cooperation needed to combat climate change, said David Waskow, director of the World Resources Institute’s International Climate Initiative. WRI is a global environmental group that conducts research on climate and energy, among other things.

“[The administration] would effectively be walking away from the greatest tool we have available to ensure all countries are playing their part,” he said.

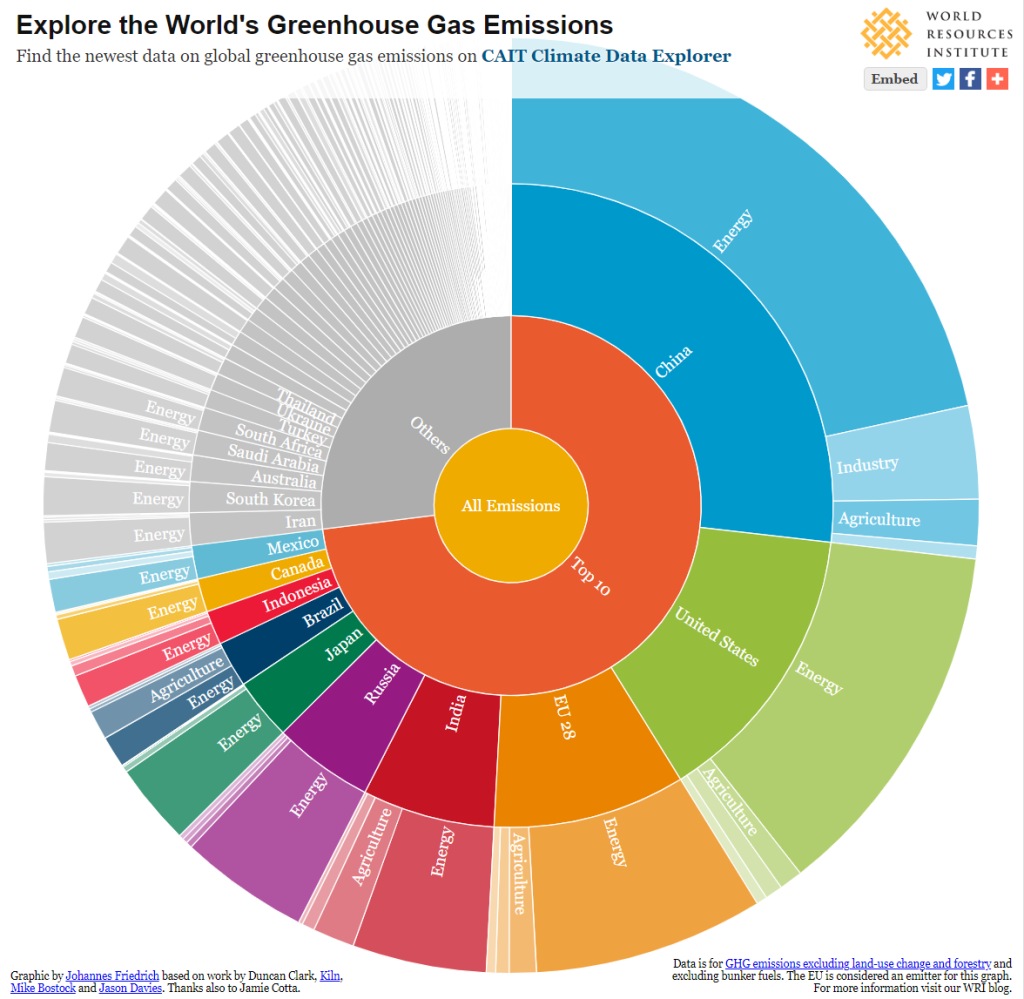

Following China, the U.S. is the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, according to WRI, with the E.U. not far behind. Together, the three contribute more than half of total global emissions, with most coming from the energy sector (think transportation, electricity generation and heating). To put this in perspective, the bottom 100 countries together account for only 3.5 percent.

As part of the accord, participating countries agree to nationally determined contributions (NDCs), which outline a country’s individual efforts to meet a climate target. For instance, one of the U.S.’s intended NDCs was to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

The U.S.’s withdrawal from the accord isn’t likely to cause other countries to abandon their targets, Waskow said. Countries have their own reasons for wanting to take action, including maintaining international relationships and reducing domestic pollution in addition to combating climate change. And many Americans support the accord: Nearly 80 percent of Americans agree the U.S. should be part of the Paris agreement, and the support is bipartisan, according to a 2018 poll by Yale. The states, cities and businesses that support the accord account for almost 70 percent of U.S. GDP, Waskow said.

Experts warn unchecked emissions will have widespread, negative impacts on the planet. A warming climate has already contributed to an increase in droughts, hurricanes and torrential rain and a decrease in biodiversity.

The Trump administration or a future administration could decide to reenter the agreement, Waskow said. But that person would need to develop new NDCs for the country to meet by 2030—and would have to set more aggressive targets to play a part in keeping the global temperature below 2 degrees Celsius.

Graphic Credit: World Resources Institute

Science-Based Stewardship in National Parks

The National Park Service passed an order in 2016 that encouraged park leaders to use best-available science when managing park resources amid a warming climate. In August 2017, the acting park service director rescinded the order to better align with the Department of Interior.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: Director’s Order No. 100

- Agency: National Park Service

- Why it matters: It influences how the NPS incorporates climate change in decision-making.

- Status: Rescinded

- Next step: The NPS could reinstate it, but there currently aren’t talks to do this.

LEARN MORE

In 2016, the National Park Service passed an order—known as Director’s Order No. 100 or DO 100—that encouraged those overseeing park resources to use the best-available science when managing the resources amid a warming climate. The rule could extend to such decisions as handling species, mitigating noise pollution or improving park meadows worn down by tourists.

This signified a major shift in NPS oversight of parks, said Gary Machlis, a Clemson University professor who worked on the order as science adviser to former Park Service Director Jonathan Jarvis, during Jarvis’ tenure from 2009 to 2017. In addition to mandating that park decisions be made using best-available science, the order elevated the role of Indigenous knowledge in decision-making; stipulated that natural and cultural resources be managed together; and required that park superintendents have some level of scientific literacy (though that requirement was loosely defined).

But in August 2017, acting park service director Michael Reynolds rescinded the order to better align park service policy with the vision set by the Department of Interior, the agency said that year in an email. Rescinding DO 100 freed the park service from a requirement to consider change in its decision-making, Machlis said.

“The lack of science, the lack of fidelity to the law and the lack of long-term public interest will have a long-term impact to the visitors and what is theirs, which is the parks,” he said. Climate change disproportionately impacts national parks, according to a 2018 study published in Environmental Research Letters. Researchers say this is largely because of the parks’ locations—they’re often in the Arctic (more than half of total national park area is in Alaska) or at higher elevation, where warming occurs more quickly due to a thinner atmosphere.

But park service decision-makers still factor in climate change, even if the issue is no longer explicitly part of a director’s order, said Cat Hoffman, chief of NPS Climate Change Response Program. She said park service staff realizes the climate is changing and that it’s affecting the parks, adding that the Climate Change Response Program—which helps national parks access information about climate change to inform decisions—is one example of how the park service is addressing climate change.

“To me, [rescinding the order] is akin to having a sign over the highway that has useful information for drivers on it that isn’t turned on,” she explained. “With or without the sign [turned on], astute drivers realize when driving conditions are changing, and they adjust.”

Jarvis said the park service was more vocal about climate before DO 100 was repealed. “My gut on why it was rescinded was that [DO 100] was basically telling the park service to be a leader … to demonstrate to the American people that climate change is real,” he said.

Based on an archival analysis, the park service has posted little new information about climate change on its website since 2017.

“I think the [new] mantra is basically: Stay in your lane … we don’t want you being a vocal, high-profile sort of spokesperson about climate change,” Jarvis said.

Oil and Gas Drilling in National Forests

A forthcoming proposal could relax a process that for years has provided a series of checks and balances for drilling requests in national forests. The proposal is meant to remove regulatory requirements and streamline decision making.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: Revised Oil and Gas Resources regulations

- Agency: U.S. Forest Service (USDA)

- Why it matters: Current regulations provide checks and balances for drilling and protect the public’s ability to comment.

- Status: Notice of proposal

- Next step: The U.S. Forest Service expects to release the proposal in 2020.

LEARN MORE

For years, requests for oil and gas drilling in U.S. national forests were subject to a series of checks and balances. For example, the Bureau of Land Management would request a drilling spot, and the U.S. Forest Service could accept or deny it after assessing environmental impact. The public often would have time to comment. In total, this process could take six months to several years, depending on the scope of the authorization, which could be for anything from small timber projects to forest plan revisions, said Marla Fox, rewilding attorney with WildEarth Guardians, a conservation nonprofit.

But a forthcoming proposal could relax that process, according to a notice published in the Federal Register. Meant to remove regulatory requirements and streamline decision-making around domestic oil and gas production, the proposal—and subsequent rule, if finalized—could also eliminate the public’s ability to weigh in on proposed leases, said Sam Evans, national forest and parks program leader for the Southern Environmental Law Center. Though the notice of the proposal doesn’t explicitly state intent to reduce public comment period, less time to comment is often a byproduct of streamlining an approval process when the purpose is to expedite it. Public comment periods can vary depending on the action, but often are between 30 and 90 days. The Forest Service didn’t provide insight on the process, despite multiple requests for comment.

The Forest Service oversees 154 national forests, 20 grasslands and one prairie. About forty-four of those properties currently have oil and gas interests or operations. Recreationists frequently use that same public land to camp, cycle, hike and run, and their experience and input can help inform how it’s managed, Evans said.

Drilling across all federal public lands contributes about 24 percent of U.S. carbon emissions (from the extraction and end-use combustion of fossil fuels).

The Trump administration claims the current requirements place a regulatory burden on energy production. Delays in requests can happen when an energy company wants to drill on forest land, but opponents say those delays aren’t necessarily connected to public comment periods or environmental regulations. They say those issues can stem from a lack of resources: The involved agencies are often understaffed and underfunded.

The proposal likely won’t be released until 2020, according to a Forest Service spokesperson. Once it’s released, it’ll be open for public comment, which likely will last 30 days.

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Regulating Methane Emissions

In August, the EPA proposed eliminating requirements for oil and gas companies to install technology to detect and fix methane leaks from wells, pipelines and storage facilities.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: Oil and Natural Gas Sector: Emission Standards for New, Reconstructed, and Modified Sources

- Agency: EPA

- Why it matters: The proposed rule would relax controls that limit methane emissions, a major contributor to climate change.

- Status: Proposal

- Next step: The EPA is expected to finalize the rule over the coming months.

LEARN MORE

In 2016, the EPA under the Obama administration created a rule that placed separate controls on two pollutants—climate-warming methane and volatile organic compounds (VOCs)—emitted during oil and gas operations. But in a move the Trump administration said will remove regulatory duplication, the EPA in August proposed relaxing the regulations that limit methane emissions.

The plan advocates for eliminating requirements for oil and gas companies to install technology to detect and fix methane leaks from wells, pipelines and storage facilities. It also calls into question whether the EPA is legally allowed to regulate methane as an emission.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that, when measured over a 20-year period, is 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide, according to the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Methane—emitted from oil and gas operations; livestock and other agricultural practices; and organic waste decay in landfills—accounts for at least 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, according to the EPA. The administration’s proposed rule would override Obama-era regulations that placed separate controls on methane and VOCs. Like methane, VOCs are gases that are emitted during oil and gas operations. They contribute to smog, according to the EPA.

The agency claims that regulating both methane and VOCs is redundant because VOC controls alone can catch methane and prevent it from escaping into the atmosphere. But not everyone agrees. Even though rules that limit methane and VOC emissions are similar, Darin Schroeder, attorney for the Clean Air Task Force, a nonprofit environmental organization, argues that both are necessary for limiting emissions because there are different amounts and types of pollutants at different stages of oil and gas production.

The separate methane regulations also are significant because they are tied to a long-term goal of regulating existing sources of pollution. Right now, the VOC controls only catch methane from new sources of the pollutant, not from existing operations built before 2015, which account for about 90 percent of methane leaks, Schroeder said.

When the EPA first created the methane rule under the Obama administration, it was a statutory requirement to eventually address pre-2015 sources of methane emissions (though a timeline was never specified), Schroeder said. If the methane regulation is repealed, the requirement to address existing sources would also disappear.

“It’s another step by the administration to ignore climate change,” he said.

The proposed rule would save the oil and natural gas industry between $17 million and $19 million a year, according to the EPA. (For reference, U.S. oil and gas revenue was between $140 billion and $200 billion between 2010 and 2018.) Not all oil and gas companies are in favor of the proposal.

BP America asked that the EPA regulate methane emissions from new and existing sources in an August statement. “Simply, the more gas we keep in our pipes and equipment, the more we can provide to the market—and the faster we can all move toward a lower-carbon future,” said Susan Dio, chairman and president of BP America.

However, Reid Porter, spokesperson for the American Petroleum Institute, said in an email to the Co-op Journal that the proposed rule could eventually help lower methane emissions by making it easier for companies to create new technologies to detect emissions.

Porter characterized the proposal as a realignment—not a rollback—of emission regulations.

“Dismissing the rule as a rollback also dismisses the effective role of technology, innovation and industry initiative in reducing emissions,” Porter said. “It discounts industry’s strong motivation to reduce emissions, which it has done in growing measure amid increased natural gas and oil production.”

Another argument for the proposed rule: It would help smaller oil and gas companies, which can have a slimmer profit margin and find it harder to meet the Obama-era emissions regulations.

Mark Boling, a consultant to oil companies trying to monitor emissions in Colorado, said it’s bad practice to cater to these smaller companies. Ultimately, the burden of complying with emissions regulations is small compared to the benefit, he said.

“It should just be a cost of business that you don’t leak this stuff,” he added.

The comment period for the proposal has ended, so it’s now up to the EPA to develop its rule in light of the comments, which will take six months or more. What will be included in the final rule remains to be seen.

Relaxing Car Emission Standards

The Trump administration in August 2018 proposed to relax an Obama-era policy that increased the national fuel economy standard. The proposed rule will also revoke the rights of states to set their own fuel standards that are stricter than federal standards.

AT A GLANCE

- Policy: The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule

- Agency: Department of Transportation and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- Why it matters: The proposed standards will lower the national fuel economy requirements, potentially allowing more pollution from vehicles.

- Status: Proposal

- Next step: Administration is in the process of finalizing proposal but exact timing is unclear.

LEARN MORE

In 2016, the Obama administration created standards to increase the national fuel economy from 35.5 mpg to 54.5 mpg for cars and light-duty trucks by 2025. The goal: reduce pollution from car emissions, a major contributor to global warming.

In August 2018, however, the Trump administration proposed to relax the Obama-era policy. The EPA and the Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration jointly published the proposal in the Federal Register in September.

The new standard lowers the national fuel economy requirements from an average of 54.5 mpg to about 37 mpg by 2025. It also revokes the rights of states to set their own standards that are stricter than the federal standards.

Transportation accounts for the largest source of human-caused greenhouse gases in the U.S., producing about 29 percent of emissions in 2017, according to the EPA. Light-duty vehicles produce the most pollutants—contributing to about 59 percent of greenhouse gas emissions within the transportation sector, which also includes emissions from ships, trucks and planes.

Pollutants from transportation also create major health risks. Air pollution from transportation and other sources kills about 7 million people globally each year, according to the World Health Organization.

In part motivated by the risks to the environment and health, 23 states in September joined a lawsuit aimed at protecting California’s ability to set emissions standards stricter than those proposed by the federal government. This would in turn allow other states to adopt California’s standards.

The lawsuit claims California’s standards “are longstanding and fundamental parts of many [states’] efforts to protect public health and welfare in their states.” The states contend that the administration hasn’t considered the damage that revoking the waiver will inflict on the environment, public health and welfare.

The Trump administration cites multiple reasons for revoking California’s emissions waiver. Chief among them is to prevent the auto industry from having to comply with multiple standards.

“One national standard provides much needed regulatory certainty for the automotive industry,” said EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler in a September statement. Essentially, if California were to continue setting stricter standards than those federally mandated for other states, automakers might feel forced to create vehicles for multiple different standards.

In the same statement, Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao said the administration’s action aims to ensure “that no state has the authority to opt out of the nation’s rules and no state has the ability to impose its policies on the rest of the country.”

The EPA declined to provide additional comments beyond the prepared statement.

Dennis McLerran, an attorney with Cascadia Law Group in Seattle, said automakers operate in a global market with more sales in China than in the U.S. With increasingly strict emissions standards in those markets, McLerran said the U.S. risks falling behind if it relaxes its own standards

He added that the administration’s other arguments—for instance, that relaxing standards will make cars safer and cheaper to buy—have been disproved by California officials.

Under the Trump administration’s proposed standards, a Consumer Reports study found that consumers would pay more overall, as compared with the existing standards. Under the current standards—which apply to 2017 to 2025 models—American consumers net $660 billion dollars in gasoline and other savings, according to the study. Consumers would lose $460 billion of those savings under the Trump administration’s proposed standards because they would be spending more each year on fuel.

On Dec. 6, President Trump said the administration next year will move to finalize the proposal. Specifics about when it will take full effect are still unclear, though the president noted he expects he will continue to be challenged in court by California state officials.

Related articles: