How a record-setting Everest expedition spawned an outdoor company with a ground-up approach to gear.

The name Sea to Summit has a great history which began in 1984 when co-founder Tim Macartney-Snape summited Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen. It’s a feat that less than 200 have ever attempted, let alone achieved. But afterward, friend and trip filmmaker Michael Dillon wasn’t impressed. Tim remembers him saying:

“Look mate, you did a pretty good climb, but you didn’t climb it properly. … The mountain is measured from sea level, and so to climb it properly, you’d really have to climb it from sea level.”

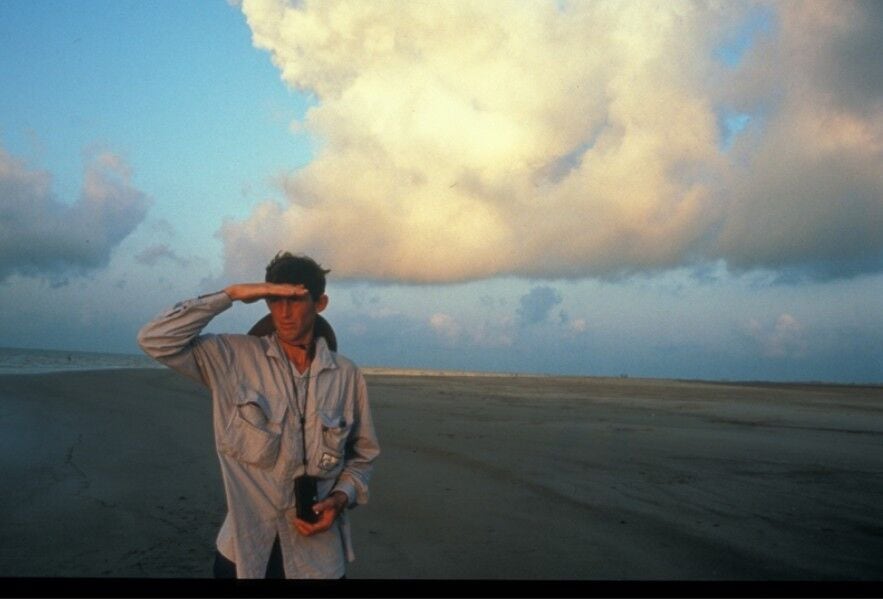

A seed was planted. Six years later, Tim found himself returning to Everest to climb the mountain, properly this time. He would start with a swim in India���s Bay of Bengal, walk over 700 miles across the Indo-Gangetic Plain, through the Himalayan foothills and climb every single one of Everest’s 29,029 feet. By starting at sea level, Tim added hundreds of miles and close to an extra 10,000 feet of elevation to the typical Everest expedition, which usually starts from Lukla at 9,383 feet.

He began walking clear across India on February 5, 1990. It was a trip of a lifetime in and of itself. Endless road miles, blisters on top of blisters on top of blisters, diminished personal space and less-than-comfortable roadside camping were just some of the difficulties. The biggest obstacle was the lack of bridge across the two-mile wide Ganges River. In order to do the climb completely self-powered, he had to swim, and became nearly hypothermic in the process.

After walking close to 500 miles in four weeks, he reached the border of Nepal. But the border crossing he arrived at was closed. In order to make it to basecamp in time, he did the unthinkable: He ran nearly 200 miles over 5 days to get next border checkpoint. That’s an average of 1.5 marathons per day for five days.

“I was on a mission. … I was kind of inspired by the fact that it was going to be a change in pace, and maybe it would improve my aerobic fitness a bit,” he chuckled.

When he reached the foothills of the Himalayas, the journey changed. He encountered rural villages, varied terrain and cooler temperatures. A week later, he finally saw the summit of Everest from afar.

“When you’re in that tepid water in the Bay of Bengal, it’s really hard to visualize or even concede that by your own effort you’re going to walk out of the tropics into the temperate zones through the foothills and end up in the so-called Third Pole,” he said. But when finally face to face with the mountain, it became clear.

Back on schedule after his “little jog,” he had a month to acclimatize by carrying gear and fixing rope higher up the mountain. He climbed from basecamp alone—deciding he wanted to discover what it would be like to take on a big mountain solo. He originally planned to summit via the West Ridge, but heavy snowfall made the route too risky as a lone climber. He changed tactics, climbing the South Col with nearly 40 pounds of gear, including a seven-pound video camera to capture his journey.

At 9:45 am on May 11, 1990 he reached the summit. He expressed his relief and the sweet realization that there was no more up. This time he said, “The place felt familiar. In ’84, it felt totally wild.”

He had two hours to contemplate the journey, as a Swedish team who summited just before him was speaking via an early satellite phone with their king and queen, giving him time to look out at the plains and think about the long journey behind him, and ahead.

“The most wonderful moment of an expedition, apart from getting to the top, is getting back down to basecamp. … Everything is beautiful. Rocks become something to wonder at rather than stumble over. And the air is like silk,” he said.

But his adventure was far from over. In fact, his journey had just begun.

“The most wonderful moment of an expedition, apart from getting to the top, is getting back down to basecamp.”

Before the expedition Tim asked his climbing partner and friend, Roland Tyson, who happened to also design outdoor gear, to make duffle bags for his gear and organizational bags for his medical supplies. When Tim got back from Everest, he realized he liked working with Roland because they “had a similar attitude towards gear: picking it apart and being really pedantic about it.”

Leveraging the notability he gained from his expedition, Tim and Roland decided to start a company called Sea to Summit named after the journey, and the rest is history.

In the beginning, they looked at simple accessories like stuff sacks and sleeping bag liners as serious categories. They knew that while other companies made accessories as an afterthought, they could make them better, more stylish and—best of all—technical.

Since day one, the ethos of Sea to Summit has been grounded in the idea behind Tim’s 1990 Everest expedition. When they create a new product, they start at “sea level” and build something great, leaving no detail untouched. From sleeping bags to kitchenware, sleeping pads to stuff sacks, Sea to Summit creates a widely diverse range of product with that same bottom-to-top attention to detail that started in the Bay of Bengal.

Earlier this year, Tim spent two weeks traveling to eight REI locations to tell his story. When asked what the Sea to Summit expedition legacy was, he humbly replied, “I’ve never really thought it was that big of a deal. … But seeing [the REI audience] reaction, I thought, ‘well, maybe it was something.’ … In the aftermath, having the idea to start a business, that’s a legacy. Hopefully it will continue and inspire others.”

Photos and video courtesy of Sea to Summit.