There is a ton of plastic making its way into our oceans every year. An estimated 8 million metric tons, to be specific. But it’s not all fishing nets, plastic straws and water bottles. Mounting evidence suggests tiny pieces of plastic are building up in our waterways. But where are they coming from?

Research indicates our clothes are a source. Every time we do laundry, hundreds of thousands of microfibers are released into the water. Microfibers are tiny strands of fabric, smaller than the width of a single piece of hair. They come from all types of materials, including natural ones, like cotton or hemp, and synthetic ones, like polyester or nylon.

These tiny natural and synthetic fibers may remain in the environment for decades, studies show. Synthetic fibers, used to create clothing that stretches and breathes, have been a primary focus of microfiber research, as they release microplastics. According to Our World in Data, most of the plastic particles in the ocean are considered microplastics. And of the particles in the Atlantic, more than 90% are fibers, per 2017 research.

“Microfibers are being found around the world,” said Genna Heath, sustainability program manager for REI. “There are still a lot of questions to be answered, but what we do know is these fibers are released from man-made products, they move into the environment where they do not readily degrade, and in some cases are being consumed by marine life.”

Though we know some things about microfibers, what’s equally troubling is what we don’t know, says Anna Posacka, research manager for Ocean Wise, a nonprofit focused on protecting the world’s oceans. We’re certain microfibers are entering our world’s oceans but we need more information about the effect they’re having—and how to reduce our impact.

That’s why REI, along with Patagonia, Arc’teryx and Canadian outdoor retailer MEC, partnered with Ocean Wise beginning in 2017 to determine how fabrics commonly used by the outdoor industry might be contributing to microfibers in waterways. The results of that study are available to the public now.

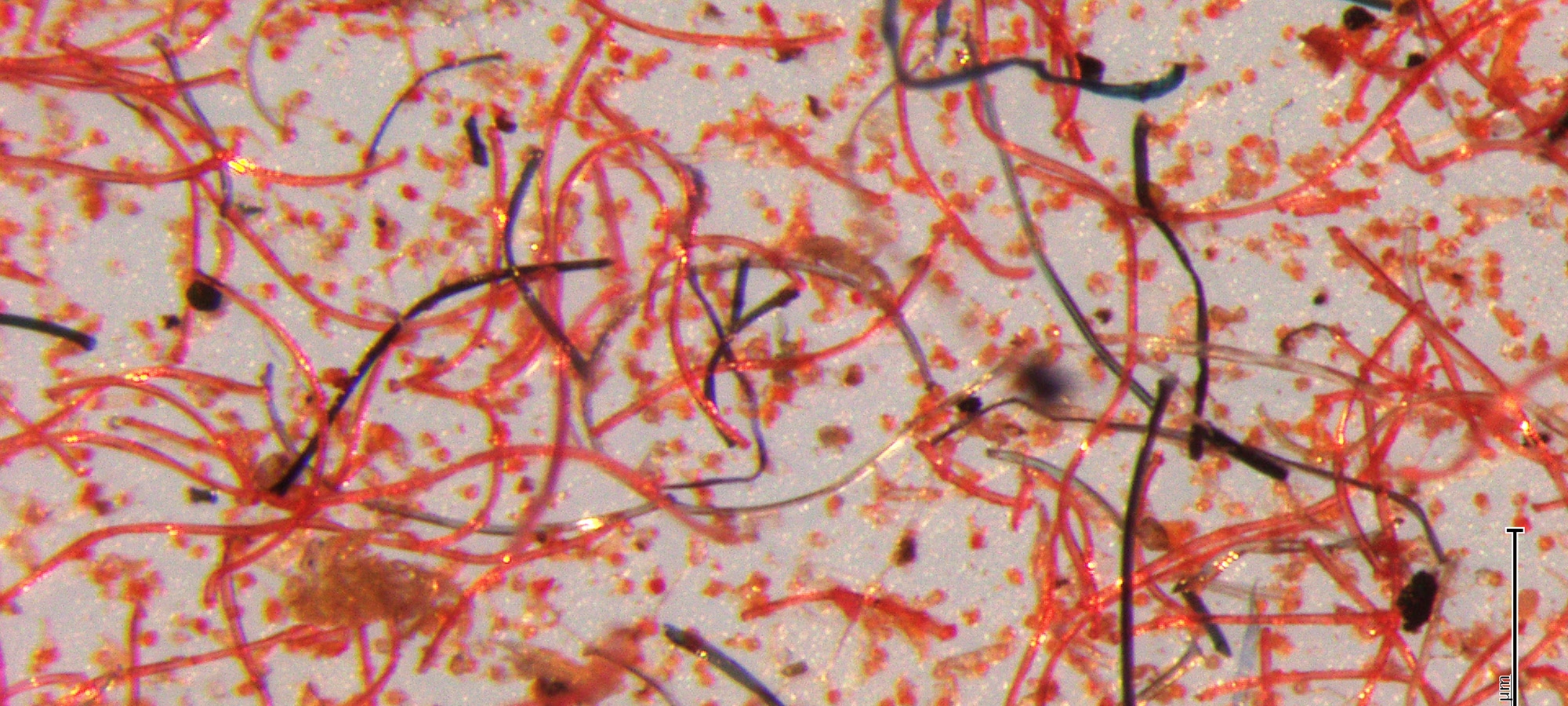

At a custom-built washing machine test facility in Vancouver, British Columbia, the study evaluated 37 natural and synthetic fabrics used to make apparel. Each fabric was washed five times. After the washes, researchers took water samples, filtered out the microfibers, dried them in an oven and weighed them. Next, the microfibers were counted under a microscope.

At the end of the process, Ocean Wise found that while all fabrics shed microfibers during a standard laundry cycle, the amount varied considerably. The range of shedding during a single wash spanned several orders of magnitude, in fact, from around 10,000 microfibers per kilogram of textile per wash to more than 4,000,000.

“The fact that some fabrics shed more than others means that there is an opportunity to explore fabric design and construction as a way to decrease fiber shedding,” said Heath.

Fabric thickness played a role in shedding, with thicker fabrics releasing more microfibers. Textile properties like construction, yarn type and mechanical or chemical treatments also influenced the degree of microfiber shedding, though more research is needed to understand exactly how much.

Equipped with this preliminary information about how textile construction contributes to shedding, designers at REI are taking steps to reimagine fabrics for the future. Already they’ve begun analyzing REI’s product line for textiles that tend to shed more, including spun/staple fleece constructions, with the goal of avoiding those textiles when designing new pieces of apparel.

But the most striking finding may have been around the potential volume of microfiber release. “In total, the U.S. and Canada combined could emit the equivalent of 10 blue whales a year in microfibers,” Posacka said. “That speaks to the importance of us thinking about our role in the issue and looking at ways to reduce microfiber pollution.”

That’s why Ocean Wise is continuing its work with a second study phase to address questions like: How much shedding comes from natural fabrics, which are also being found in increasing numbers in the ocean? How do different textile manufacturing practices influence shedding? And, how can textile designers choose fabrics based on how likely they are to shed?

As for the last, the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) RA100 working group, which REI has been part of since 2017, is developing a standardized test to measure shedding from textiles. Heather Shields is the chair of this working group and said that in the coming months, the AATCC plans to release a global industry test standard to help designers assess fabric shedding.

“Having this test will be great because it will give us quantifiable data to use,” said Soojin Chung, manager of materials for REI Co-op Brands. “Instead of us guessing or assuming certain material may be prone to higher shedding, we’ll have quantifiable data to make design decisions.”

Karinda Robinson, director of product strategy for REI Co-op brand apparel says the co-op will use the AATCC method to continue to pursue its goal of making products with the least environmental impact. “We are on a mission to make the best quality, most sustainable gear,” she said. “This test will be a huge piece of that. It’s going to change how we build product and how we select materials.”

While REI and others work on finalizing a standardized testing method, the REI Co-op materials team is collaborating with its manufacturing partners to devise new ways to keep microfibers from entering waterways before they ever reach a customer’s home. Some partners are working to install vacuums to remove microfiber shed while fabrics are being made. Others are exploring washing materials with specialized filtration systems before they are released to the market, as research shows most shedding happens during that first wash.

“This issue is daunting, but it’s also an area where different people, brands and industries are coming together to take action,” Heath said. “I’m excited to see how this type of collaboration catalyzes innovative solutions.”

For ways you can help reduce your impact at home, refer to Ocean Wise’s four key practices:

- Wash your clothing less often. Since home laundering releases microfibers, an easy way to stop your footprint from growing is to simply get more use out of your clothes between washes.

- Buy clothing that lasts. The more textiles we buy, the more textiles (and thus microfibers) are created. When you resist fast fashion by purchasing apparel that stands up to the test of time, you’re reducing your impact.

- Use a front-loading washer. Research tells us that a front-load washing machine can result in 5 times less microfiber shedding than a top-loading one.

- Invest in a microfiber filter. The LANGBRETT Guppyfriend Washing Bag filters out the microfibers released during machine washing and is available at REI.com at the wholesale price. You can also invest in a filter (like this one) that is permanently installed near your washing machine.