We all have dreams, aspirations—a bucket list. Before signing up to climb Kilimanjaro, I had been interested in mountaineering for a few years. Then, at the 2016 Outdoor Afro Leadership Training, I learned that I could apply for the opportunity of a lifetime—the chance to climb Kilimanjaro with Outdoor Afro. Little did I know I was about to join a team of 11 leaders who, by the end of the expedition, would become family. We would be the second all-Black U.S. expedition team to climb Kilimanjaro.

I can still remember the moment I learned I’d been picked to join the expedition team. I was on my way to lead an Outdoor Afro event in Baltimore, Maryland. Before heading out, I checked my email one last time and saw a letter congratulating me on making the team. Suddenly, I was feeling so many things—shock, excitement and a little fear.

Training: Adjusting to Running

My training started in August 2016. I struggled to figure out how to train for a high-altitude climb of more than 19,000 feet while living in Washington, D.C. Many people told me: Go to Colorado and hike 14ers—you’ll be ready in no time. For me, this wasn’t a practical solution. I’m a preschool teacher and an Outdoor School instructor for REI. Taking time off work, renting cars and paying for flights—the costs added up quickly and made me anxious. I went back to the drawing table. I was inspired not only to do the expedition for myself, but also to bring back knowledge to my community—so they would have the tools and inspiration to do it as well.

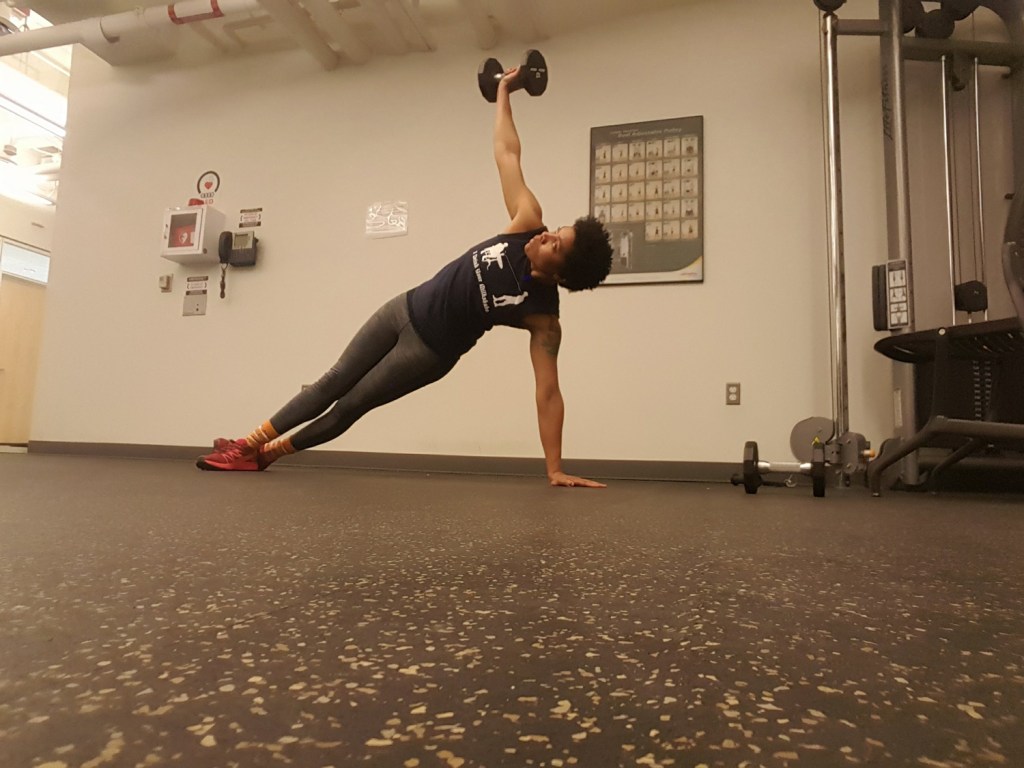

The author combined running and weight training in her hometown of Washington, D.C., to prepare for the high-altitude climb. (Photo Credit: Brittany Leavitt)

Our group would be traveling the high-altitude Machame route to climb Kilimanjaro—a route that requires great endurance. An internet search revealed the best way to develop endurance was running. At the time, I honestly hated running, especially on the treadmill. I told myself: If I am going to have to add running to my training, I’m gonna find a space where it will be smooth for me. I ended up doing a combination of running and weight training, beginning on the National Mall. I’d never been at an elevation higher than 7,000 feet, so I challenged myself on stairs and by walking on the treadmill on a 15 percent incline with a weighted pack on my back. I also hiked in Shenandoah National Park.

To say that I headed straight to training after work each day would be a great lie. It took a little while for my body to adjust to the routine. There were days and weeks when I needed a break and would head to the climbing gym—or just go home. Once February hit, I told myself I couldn’t be lazy anymore. I started training three days a week for two hours after work. Sometimes, I would head to the mall early in the morning for a nice run and then hit the gym after. By the time June 2018 rolled around, I felt ready. One year of training had prepared me for the next seven days.

Preparations: Moving Slowly, Slowly

The entire Outdoor Afro Expedition Team gathered at a hotel in Arusha, Tanzania. There, we spent one night, packing and making last-minute preparations. My goal was to cut down my weight and only carry necessities. My pack weight ended up being 25 pounds. We also had our daypacks, which we filled with our Ten Essentials, plus all-weather gear since we didn’t know what to expect.

Phil Henderson and Rosemary Saal, two of our expedition leaders, helped us assemble ourselves. There were so many little moments of anticipation and excitement that made what we were about to do more real. We had a sit-down meeting with our guides. We talked about what each day on the mountain would look like, what we would eat and how altitude sickness is no joke. We were encouraged to drink water and eat at every meal. We were told to climb slowly or pole, pole (which means slowly, slowly in Swahili).

The Climb: Finding a Groove

The next day, we headed to the mountain. When we arrived at Kilimanjaro National Park, we met our porters and guides. But we didn’t start climbing right away. We ate lunch and made sure our gear was packed and ready. We had a chance to meet the park superintendent, who told us a beautiful story about the importance of Kilimanjaro and how the glacier is a major resource to the surrounding villages. The superintendent told us we were now officially the ambassadors of the mountain. That was an incredible moment, one to cherish always—when we became ambassadors to the tallest freestanding mountain in the world.

The night we made it to our first camp was so magical. I am someone who is in love with the solar system and the constellations. This was the first time in a while that I could see the Milky Way. Seeing the stars all clustered together made the night sky seem unreal. I spent every night on Kilimanjaro stargazing and watching shooting stars.

Like with any expedition, it took a little while for our 11-person group to find our groove. Ahead of the trip, we’d talked on the phone, thanks to the help of two more leaders, Chaya Harris and Katina Grays. We had come to Kili from across the entire U.S., varying in ages and experience. We had trained the best we could in our own spaces. Now, on the mountain, we quickly learned about each other. We shared many tears as we struggled to figure out each other’s comforts, strengths and abilities. We also experienced loss, as two of our teammates had to head down the mountain due to hydration issues and altitude sickness. The mountain gave us a space where we could laugh, cry and sing.

The Outdoor Afro team at Barafu Camp at 15,331 feet. (Photo Credit: Chaya Harris)

We lucked out on the weather and our route, which is one of the more popular ways to climb Kilimanjaro. If forced to choose a day that was my favorite, it would be day five, when we got to do a bit of rock scrambling up the Barranco Wall—an 800-foot scramble that took about two hours. It was so cool to look over and just see nothing but rocks and clouds surrounding us. It felt like we were in our own world. The porters were truly inspiring to watch run up the wall. After the scramble we walked down the Karanga Valley. I loved how you could see the trail ahead of us winding around the mountain. That day, we only went about three miles but it took us roughly five hours to get to our next camp.

Summit Day: Reaching 17,000 Feet

Day seven was summit day, and a lot was going through my head—this was the day. My nerves kicked in as we made our way to our campsite and saw people coming down from the summit. We had pasta for dinner, but I only took a few bites as my stomach wasn’t letting me eat. We were set to head out at 11pm. I tried to take a power nap, but the winds had picked up, and I was worried. My body takes a while to warm up and I have poor circulation in my hands and feet. I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to move my feet or hold on to my trekking poles. But it was time to leave. I made sure to layer my hands and toes with extra protection, and I put on my balaclava to help keep my face as warm as possible. We had one last meeting in the tent, with cookies and tea. Our guides encouraged us to take a few cookies in our pockets for fuel on the way up. Then, we started our trek.

Right away, the wind was horrible. We couldn’t see anything around us—just the headlamp of the person ahead and a line of lights from other teams below. My hands started to freeze and were barely holding on to my trekking poles. I kept telling myself: You cannot quit. You’re so close. You can power through. At some point, it began to feel like the wind was taking my breath away. I took deep breaths in through my nose and out through my mouth. But it wasn’t happening. I started to feel nauseated.

We stopped, and our guide was letting us know we could see snow. This meant we were getting close to Stella Point, where we would watch the sunrise. I wanted to feel excitement, but my brain was in full panic mode. The only word I could say was, “Yup.” I turned to Chaya and told her I needed to sit. Sitting turned into passing out in Chaya’s arms. I remember waking up on a rock where Phil was asking me questions. The guides were discussing if I should go on. They finally made the decision that I had to turn around. This was it—this was where my body was telling me I would summit. I cried. My goal had been to reach Stella Point, which was over 18,000 feet. It turns out that I reached my summit at 17,000 feet.

I remember one of our guides saying. “It’s just a sign at the top. Your health and well-being are more important than reaching a sign. You can come back and try again.” At the time, it was hard for me to process these words. I knew that I would not want to go back. Climbing with the team was such an experience—I knew I wouldn’t want to try to re-create that for myself.

The Descent: Only a Few Hours

As I trekked down to our camp, my body began to feel better. I had the urge to tell the guide who was walking me down, Let’s turn around! I feel fine! But I realized that I had to set my ego aside. Losing my fingers—or even my life—wouldn’t have been worth it. As we trekked down farther the next day, I was quiet for a while, reflecting on the previous night. I felt defeated and angry with myself. I kept replaying my experience on the mountain. Finally, our whole team reassembled at Mweak Camp at 4,600 feet. It was such a good feeling to have everyone back and feeling healthy. The next day, our team hiked down through the jungle to the park’s main entrance. Even though I hadn’t made it to Summit Point of the mountain at Uhuru Peak, we had climbed Kilimanjaro.

The author, on day 7, descending from Barafu Camp. (Photo Courtesy: Brittany Leavitt)

Summiting a mountain is only a few hours of any expedition. The journey toward our goal was more impactful. For me, the trip hadn’t just been about climbing Kilimanjaro. This had been my first overseas trip and part of what had made it so special was discovering a connection to our motherland, Africa. Returning to the U.S. from Tanzania, our team brought back so much love, dedication and Black joy.

In the end, five out of 11 of our teammates pushed their way to the summit. Many of the people who summited aren’t your average backpackers or hikers, which made the summit even more special. Yes, the summit had been an accomplishment, but it was also about inspiring my community and showing that dreams are attainable, no matter what. I made it to 17,000 feet on Kilimanjaro and I am proud of that.