In California, the Mendocino Complex Fire, the largest wildfire in the state’s history, has burned more than 300,000 acres—largely on national forest land—and another wildfire has shut down part of Yosemite National Park indefinitely.

There are 14 fires burning across the state, causing smoke to blow over much of the West. Some of the heaviest smoke is settling in Northern California and in Sacramento County, centrally located between several of the state’s largest fires, where the population is 1.5 million and health officials are recommending people stay inside. (For updated air quality conditions, visit AirNow.gov.) Combined with temperatures in the 90s, haze and air quality are forecasted to get worse as the weekend approaches. The poor air quality is enough to encourage people to cancel their weekend plans and stay indoors. But these huge, destructive wildfires—called a “new normal” by Governor Jerry Brown—may have an even longer-lasting effect on recreation. In California, officials have closed huge areas of public land that encompass campgrounds and hiking trails, while flames continue to burn in national forests and edge up to wilderness areas.

“The typical pattern we’re seeing in fires is aggressiveness,” said Scott McLean, a spokesperson for Cal Fire. “The severity in how they burn, extremely hot, and the destruction that follows them. Even the smaller fires are causing evacuations to take place, which we have not seen in years past.”

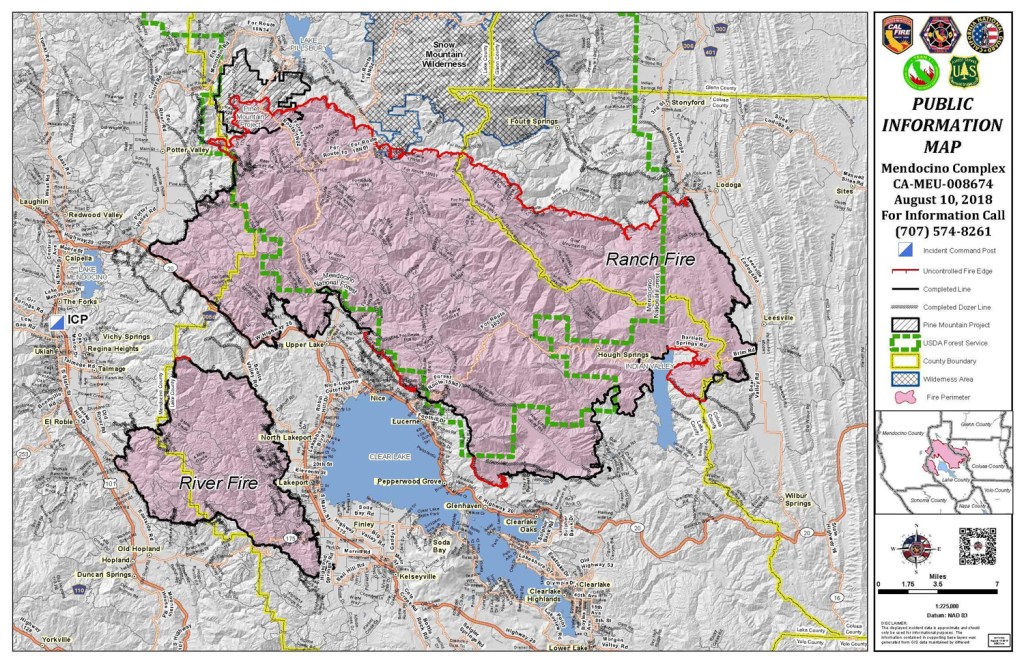

Mendocino Complex Fire Public Information Map. Courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service.

The Mendocino Complex Fire, about 100 miles north of San Francisco, surpassed Ventura’s Thomas Fire this week to become the largest fire in modern state history. Fueling the blaze’s growth, McLean cited hot, dry weather and erratic wind. The complex is two neighboring fires that started within an hour of each other on July 27 and, together, they have burned an area comparable to the size of Los Angeles. But in terms of destruction, the Mendocino Complex Fire has not claimed as many structures or homes as other infamous California blazes this year and in years past. Instead, the fire is largely burning in rugged, remote forest.

The larger of the two fires in the Mendocino Complex, the Ranch Fire, is located on the southern end of the Mendocino National Forest, located in the mountains about 80 miles east of the coastline. The forest hosts campers, hikers, mountain bikers, anglers and off-road drivers, among many other recreationists. As of Friday morning, the Ranch Fire had burned 258,562 acres, and after working nonstop for two weeks, firefighters had contained 60 percent of the complex. Yet, even as efforts to contain the fire made progress, earlier this week the flames stretched further north and crossed into the Snow Mountain Wilderness, where heavy smoke prevented aircraft from flying.

Campgrounds, trail systems and an entire network of roads for off-highway vehicles are all within the boundaries of the closed part of the forest, said Punky Moore, the public affairs officer for the Mendocino National Forest. The Bureau of Land Management also issued sweeping closures of campgrounds, equestrian areas, waters, wilderness and wilderness study areas because of their close proximity to the Mendocino Complex Fire.

“Because of the size and the extreme fire behavior and the small amount of containment, we’ve had to put in significant area, road and trail closures,” Moore said. The northern half of the forest, which is nearly all wilderness area, is still open to the public. But Moore recommends that people exercise caution, check fire restrictions and area closures, make informed decisions about recreation, and be wary of smoke and unhealthy air.

“We’ve certainly had fires in the forest before, but nothing that compares to this one in a while,” Moore said. “It’s spreading very fast. It’s spotting out in front of itself, which means it’s throwing embers way out in front of the main fire and starting new fires.”

Jesse Rathbun is a bike mechanic in Boonville, just west of the Mendocino Complex Fire. “The sun is bright red now. It’s pretty trippy,” Rathbun said on Wednesday morning. He was working a shift in the bike shop he owns called Boonville Bike Works, and business was slow. “There are still people riding bikes, but less. … Some of us are a little stir crazy.”

It’s been a year since wildfires struck in Santa Rosa, and those trail networks are just starting to reopen, Rathbun said. “It’s open, but it’s not repaired,” he said. “There’s a lot of damage. Trees are down, brush, piles of ash, piles of burned crap everywhere.”

A red sky hangs over Mendocino County, CA. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Forest Service.

In the Mendocino National Forest, Moore said it will take a lot of time to figure out what areas and trails the Forest Service can reopen and when. “We can only open up areas when we can determine that they are safe, and that could take some time,” said Moore. Especially as the fire burns north and reaches parts of the forest that are harder to access, getting to those places to assess damage and reopen will take a lot of time.

About 300 miles south of the Mendocino Complex Fire, the Ferguson Fire has burned more than 95,000 acres at Yosemite National Park since July 13 and is now the largest in the history of the Sierra National Forest. Firefighters took advantage of higher humidity this week to contain the blaze. Calling the fire activity inside the park “dynamic,” national park officials have shut down popular areas in Yosemite National Park indefinitely. In a statement, officials described flames that are consuming dead and downed trees with explosive energy. Yosemite’s terrain and shifting weather further complicate fire suppression efforts and tactics.

Fires have also shut down sections of the Pacific Crest Trail in southern California near Idyllwild and in the High Sierra between Sonora Pass and Ebbetts Pass. If and when hikers do encounter a wildfire on the trail, the Pacific Crest Trail Association recommends quick action and warns hikers to stay away from windy ridges, make yourself visible to firefighters, and find shelter in places with less vegetation like a meadow or a flat rock.

In general, Moore recommends that campers, hikers and recreationists pay close attention to fire restrictions. Forest and fire officials put those restrictions into place based on a variety of factors, she said, including how dry the timber and fuels are and whether the forecast is predicting precipitation. “As things dry out, every year we start to see the same kind of trend,” said Moore, noting that, this year, fire restrictions went into effect on July 6.

“As soon as we go into fire restriction, that should be a sign to people that we are coming into the fire part of the year where we all have to be super careful,” Moore said. “There’s the increased potential to have fires on the forest, and so for me, and hopefully our visitors, that’s the first sign.”

How to be fire safe, from the U.S. Forest Service

- Before hiking or camping, check with the forest, grassland, or ranger district for fire restrictions or area closures.

- Plan ahead and prepare—know your route, and tell a responsible adult where you are going and when you plan to return.

- Sign in at the trailhead.

- Use alternatives to campfires during periods of high fire danger, even if there are no restrictions. Nine out of 10 fires are caused by humans.

- If you do use a campfire, make sure it is fully extinguished before leaving the area—be sure it is cold to the touch.

- If you are using a portable stove, make sure the area is clear of grasses and other debris that may catch fire. Prevent stoves from tipping and starting a fire.

- Practice Leave No Trace principles—pack out cigarette butts and burned materials from your camping area.

- Beware of sudden changes in the weather or changing weather conditions. For example, if you see a thunderstorm approaching, consider leaving the area. Fires started by lightning strikes are not unusual.

- If you see smoke, fire, or suspicious activities, note the location as best you can and report it to authorities. Call the National Fire Information Center or 911.

- Do NOT attempt to contact suspicious people or try to put out a fire by yourself.

- Be careful of parking or driving your car or ATV in tall, dry, vegetation, such as grass. The hot underside of the vehicle can start a fire.