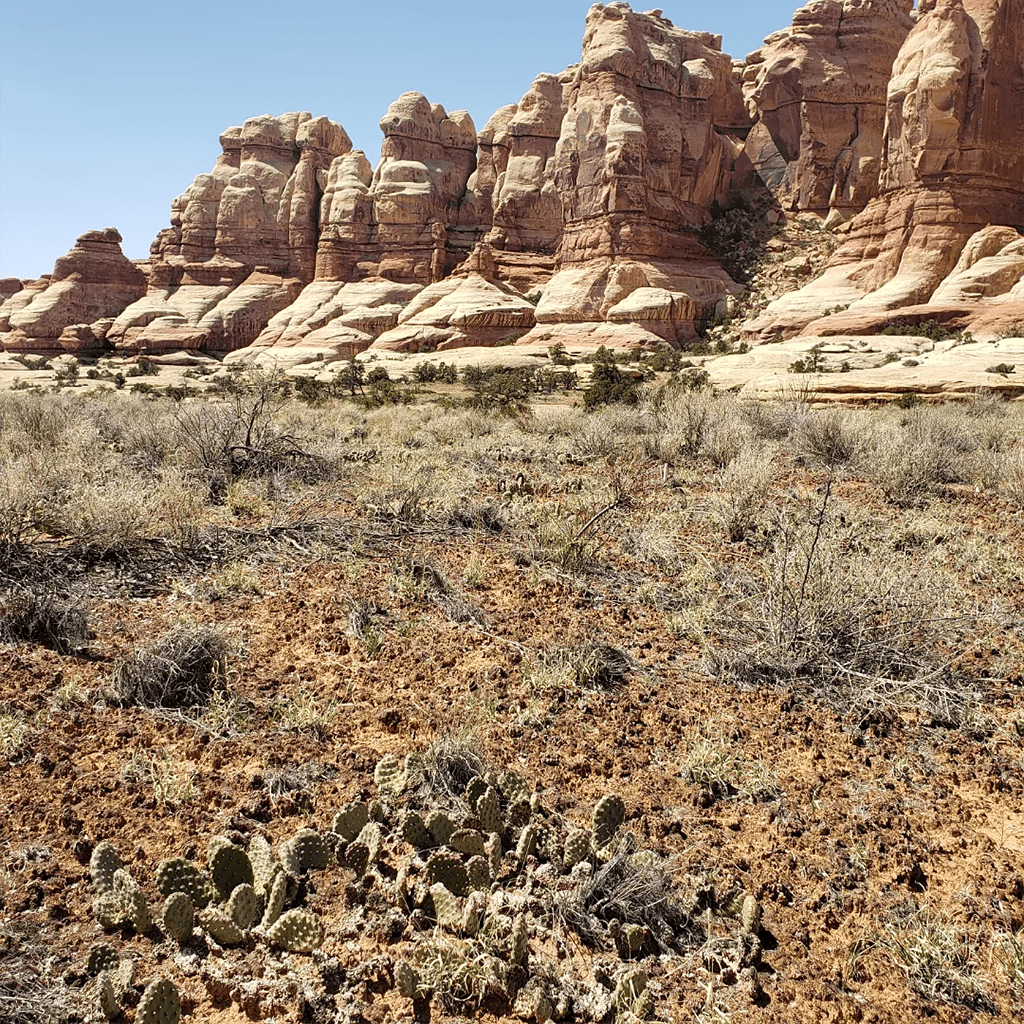

Red stone arches, towers and cliffs seem to puncture the endless blue skies around Moab, Utah. But for Rebecca Finger-Higgens, Ph.D., another, much smaller, landscape is especially beautiful—the bumpy, lichen- and moss-encrusted top layer of the soil. This is biocrust.

This layer, less than an inch thick, is much more than just dirt: It’s a community of “really complex, beautiful organisms,” explains Finger-Higgens, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The mosses in biocrust may appear dark brown at first, but will light up like little green stars when you drop water on them. Biocrusts also typically include lichens ranging in color from black to pink to yellow. “They’re kind of like these mini mountain ranges—kind of like coral reefs of the desert,” she continues.

Essential to supporting ecosystems, these mini mountain ranges span beyond the Colorado Plateau, across the arid lands of the American West and are found in all dry regions of the world. While they are remarkably resilient to drought, heat and the forces of wind and water, soil biocrusts are vulnerable to the impacts of hooves, human feet and tires. These forces can crush them, breaking apart the tight network of organisms and leading to their starvation. If they manage to recover at all, full regrowth can take hundreds of years.

That’s why, in places like Moab, scientists and advocates are trying to prevent biocrust loss. Even stopping a single stray footstep makes a difference.

Biocrusts: Enigmatic but Essential

What even are these tiny marvels? They’re a colony of tiny organisms, most of which are microbial. Biocrusts generally include bacteria, fungi, lichens and mosses, though the individuals making up the community vary depending on their surroundings.

The organisms work together to survive in their often-harsh environment. Mosses are photosynthesizers, making sugar to feed the biocrust, and lichens—themselves a partnership between a fungus and a microbe—obtain nitrogen from the air. Certain bacteria create filaments that stick the soil surface together, almost like a thin fabric coating the ground.

Soil crusts are found on every continent and are linked by a common purpose: stabilizing the soil.

Particularly in arid regions, where plant coverage tends to be patchier, biocrusts carpet the bare soil, protecting it from the ravages of wind and water. In fact, most deserts—including those of the American West—are not inherently dusty places, despite how they’re often depicted in movies and TV, explains Jayne Belnap, Ph.D., a USGS ecologist who’s been studying soil crusts for the past 30 years. Rather, dust storms tend to form where biocrusts have been busted by grazing, military use or other disturbance, leaving loose and exposed soil that flies away when windy.

This stabilizing function is also crucial because desert soil forms at an excruciatingly slow pace: It can take a century for a single centimeter of soil to form, explains Belnap. Meanwhile, a whole meter of soil can be lost when a ferocious windstorm bears down on the exposed surface. The top few centimeters of the ground, including the biocrusts and the soil directly beneath them, hold nutrients and sponge up water needed for plants. “When you watch that dust cloud go by or you watch the flash flood go by, what you’re seeing go by is the productivity of that ecosystem,” says Belnap.

Beyond serving as the skin of the desert, biocrusts also add nutrients to the soil. Nitrogen, for example, forms the backbone of DNA and is a building block of proteins—and it’s also particularly hard to come by in arid lands. Microbes called cyanobacteria that are part of the lichens in soil crusts can transform nitrogen in the air into a nutrient that plants can use to support photosynthesis.

Biocrusts themselves also photosynthesize, capturing carbon from the atmosphere and incorporating it into their biomass and the soil. Some of the lichens in biocrusts even produce special pigments that serve as sunscreen, protecting the organisms from harmful UV rays.

Biocrusts tend to be pretty hardy, able to survive on just a couple inches of rainfall per year. They endure the hot and dry months by entering a dormant state; when rain does fall, the moss on the crusts’ surface blinks awake, turning green as it begins to photosynthesize, making enough sugar to last the community through another dry stretch.

The Threat Posed by Desert Recreation

Drought and extreme heat are generally no problem for biocrusts (though rising summer temperatures may pose a threat to some), but they do have archnemeses: hooves, heavy vehicles and, increasingly, hiking boots.

In recent years, more and more visitors have flocked to Moab, Utah’s red landscapes. Last year, visits to the region clocked in at more than 3 million. The crowds sometimes inspire tourists to drive and trek out beyond the bounds of established trails and campgrounds. In areas administered by the Bureau of Land Management, such as along Willow Springs Road, things have been especially bad: Finger-Higgens says people there have been parking cars outside the bounds of existing roads and campgrounds, bringing in fire rings and leaving behind their poop, and in the process driving and stomping over biocrusts.

And soil crusts can be lost even without direct impact. During construction of the campgrounds and trails at Sand Flats Recreation Area in the 1990s, the resulting pink dust coated parts of the surrounding area, says Dr. Belnap. This dust prevented the biocrusts below from absorbing sunlight, leading them to essentially starve. Red dust from disturbed Moab soils has even been found speckling the snow more than 400 miles away in the Rocky Mountains, says Dr. Kristina Young, executive director of Science Moab, a new nonprofit dedicated to making place-based science within the Colorado Plateau accessible to the greater public. Since it’s darker in color than snow, the dust absorbs more heat and can cause accelerated snowmelt.

Once a landscape is devoid of crusts, it’s hard for them to build up again, especially if the soil has been compacted from repeated travel. In former military training grounds in the Mojave, Dr. Belnap has observed minimal crust recovery even after 50 years—and she estimates it could take hundreds of years for the communities to come back.

Walking Lightly to Protect Biocrusts

So far, scientists’ efforts to regrow biocrusts have had mixed results at best: While it’s relatively easy to grow them in a lab, it’s hard to get biocrusts to take hold in the wild, says Belnap. Since they’re so hard to restore, it’s important to avoid crushing crusts in the first place. “It’s pretty clear to me that you just can’t wreck them.” That’s why scientists are working to educate visitors on these remarkable groups of organisms and hopefully prevent further loss.

Belnap has led education efforts since the ’80s: While visitors might not have any idea what biocrust is when they arrive at the trailhead, they’ve been incredibly receptive when given information, either on flyers or posted signs. Belnap has even squeezed in educational material in town, such as at local bike shops.

Unfortunately, such efforts require a steady stream of funding, and park budgets have stagnated, says Belnap. “We were much more effective when there was a lot more money around,” she says.

In recent years, however, new crust protection efforts have sprouted. Some of Grand County, Utah’s tourism revenue is diverted to its trail ambassador program, launched in 2021: County educators, trained by Science Moab staff, set up at trailheads with a sample of biocrust in hand, ready to inform visitors about the sensitive soil communities.

In addition to working with the trail ambassadors, the Science Moab team also leads science training for guide companies, including those leading mountain biking, climbing, rafting and overland tours.

“There’s this really cool science that says when you’re having an adventure or an outdoor experience that’s new to you and is a fun experience, that you are able to retain information better,” says Kristina Young, Ph.D., Science Moab’s founder and executive director. She says guides can serve as a conduit for information on protecting the desert. “I just have no doubt that it is making an impact.”

As for what desert-bound adventurers can do to protect these complex microorganism communities, soil scientists say that the first step is to simply marvel at soil crusts when you encounter them. Get close enough to view them from a rock or the trail—just remember to step carefully. “Take a minute and look around and see, maybe you’ll notice some pinks and yellows, and those little beautiful features of the landscape,” says Finger-Higgens.

Once you’re done admiring them, stay on established trails, roads and in existing campgrounds. In areas where restrooms are unavailable, it can be better to pack out solid waste and paper using a waste bag than hike off the trail and dig a cat hole. If you need to stray beyond the trail or campsite bounds, hop between rocks, logs and the bottoms of washes instead of touching down on the soil. Even if the soil isn’t bumpy and dark, there could be less-developed soil crusts present. In drier deserts, like the Mojave, soil crusts are often nearly invisible.

“The plants and animals and biocrusts here are all adapted to live within these harsh conditions, which means that they’re sensitive to change because they really are in this narrow zone of where they can survive,” says Finger-Higgins. “So it’s important to respect that and to really consider where you’re going.” Just a few extra precautions can allow the biocrusts—and the ecosystems they support—to continue thriving, preventing the desert from becoming dusty and barren.