A version of this story appeared in the winter 2020 issue of Uncommon Path.

At the Kearsarge Pass trailhead in the high alpine outside Independence, California, we smudge ourselves with sage and prepare for our 12-mile journey. The sun is already high in the sky, and the desert air feels thin as we hoist our 40-pound packs and start walking down the dusty path.

It’s late August 2018, and I’m one of a handful of people carrying a resupply of dehydrated food, moleskin and sunscreen for a group of Indigenous women who have been trekking through the Sierra Nevada. The group is due at Bullfrog Lake in 10 hours, where, as night falls, we’ll hand off the reserves we carried and pray for the final 30-mile leg of the women’s trip before they take off for the southern terminus of the John Muir Trail (JMT).

The JMT is one of the most popular long-distance hiking paths in the American West, but the women aren’t there to recreate. They’re with a grassroots organization known as Indigenous Women Hike, reclaiming their ancestral trade routes. Our Nüümü (Paiute) elders have called the JMT the Nüümü Poyo—the People’s Trail—for as long as I can remember, as it’s part of a network of routes in the Sierra that have been used by tribes for hundreds of years. In walking the more than 200-mile trail, the women, my friends, will honor their ancestors and restore the region’s Indigenous place names. At the end of the journey, they’ll summit Tumanguya, the Newe (Shoshone) name for Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the 48 contiguous United States at 14,494 feet. It will take them three weeks if all goes to plan.

The Ahwahnechee, Paiute, Miwok, Mono and other tribes inhabited the region in and around the Sierra Nevada for centuries before Europeans set up permanent settlements in California in the mid-1700s. By the time conservationist John Muir first visited the subalpine fields of central California’s Tuolumne Meadows roughly a hundred years later, Native people had been working with the land for millennia, promoting ecological diversity and stewarding the forests. When Muir passed through the Range of Light in 1868, he was struck by the beauty of the environment and assumed nature simply manicured herself.

Muir, who is often considered the father of our national parks, became one of the region’s most ardent advocates, with his writings influencing Congress to establish Yosemite National Park in 1890. At that point, a concerted effort to eradicate Native tribes from the region was underway. An 1850 California law made it legal to enslave Indigenous people for their own “protection,” and in 1851, the first California governor armed local militias against Native tribes, using a state address to proclaim that a “war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

Happy Isles Bridge, the starting point of the Nüümü Poyo. Indigenous groups inhabited the region around the Sierra Nevada long before before Europeans settled in California. (Photo Credit: Benjamin Rasmussen)

Not only were California tribes like the Ahwahnechee removed from their homelands, but between 1846 and 1873, they were also stripped of their identities and languages, both of which were directly tied to the land. Tribes often ended up on small reservations, or without any land to call home at all.

In June 2019, California’s brutal history was finally acknowledged by Gov. Gavin Newsom, who publicly apologized for the estimated $1.3 million spent in the 1800s to fund “a war of extermination” against Native people in California. In Newsom’s own words, “It’s called genocide. … [There’s] no other way to describe it.”

In a high-desert basin tucked between the White Mountains and the Eastern Sierra, I learned what was left of my language, and my teachers instilled in me respect for our land and water. I went to sweat lodge, danced at powwows and ran barefoot through fields with my cousins. I harvested wild pine nuts and tea. Even since moving away for college and work, I’ve always returned to these mountains when I’m lost, hurt or need to heal.

My ancestors are Diné (Navajo) on my mother’s side, from the American Southwest, where, in 1864, our people were forced at gunpoint to walk hundreds of miles to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, and incarcerated until 1868, when our people walked home to northern Arizona. On my father’s side, my ancestors are Nüümü and Apache. The Nüümü people were forced to walk 250 miles south to Fort Tejon, California, in 1863, to make way for settlers and miners. All of my tribes were held as U.S. prisoners of war after being marched off their land. Walking is in my blood.

The women confronted reminders of unfreedom amid the breathtaking scenery. Some trail signs evoked derogatory images of Native people, and many markers stripped the land of its Indigenous place names. (Photo Credit: Benjamin Rasmussen)

In a way, so is bringing resupplies. In November 2016, my mother, my childhood friend Jolie Varela (citizen of Tule River Yokut, Nüümü and Arapaho) and I traveled to the Oceti Sakowin camp on the Standing Rock Sioux Nation to deliver winter clothes and food to demonstrators advocating against the development of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

People around the world were responding to the protest’s primary message, “water is life,” as they learned of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s fight to protect its water supply from an oil pipeline proposed by Texas-based Energy Transfer Partners. The mission resonated deeply with Jolie, as our own Nüümü region faces an ongoing water-rights dispute with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Jolie approached me with bright red cheeks and a big smile the morning I left Standing Rock. Her breath smoke drifting in the frozen morning air, she handed me two pairs of beaded earrings and said, “Hang on to these. I’m staying.”

After three months of subzero temperatures in a mock tepee made from a tarp, Jolie envisioned an idea to renew her relationship with her ancestral territory. She planned to hike the Nüümü Poyo in an effort to heal herself through connection with the land and bring awareness to the environmental injustice against our own community—an act of cultural reclamation.

Jolie Varela, the founder of Indigenous Women Hike. She began connecting to her homelands through hiking in her late-twenties. (Photo Credit: Benjamin-Rasmussen)

And so on Aug. 3, 2018, the air heavy with plumes from the nearby Ferguson Fire, Jolie and two other Indigenous women, Autumn Harry (citizen of Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, Numu, Diné) and Amelia Vigil (Picuris Pueblo and Purépecha heritage, Two-Spirit), met at the Tuolumne Meadows trailhead in Yosemite National Park to begin their 200-plus-mile trek, the inaugural journey of Indigenous Women Hike.

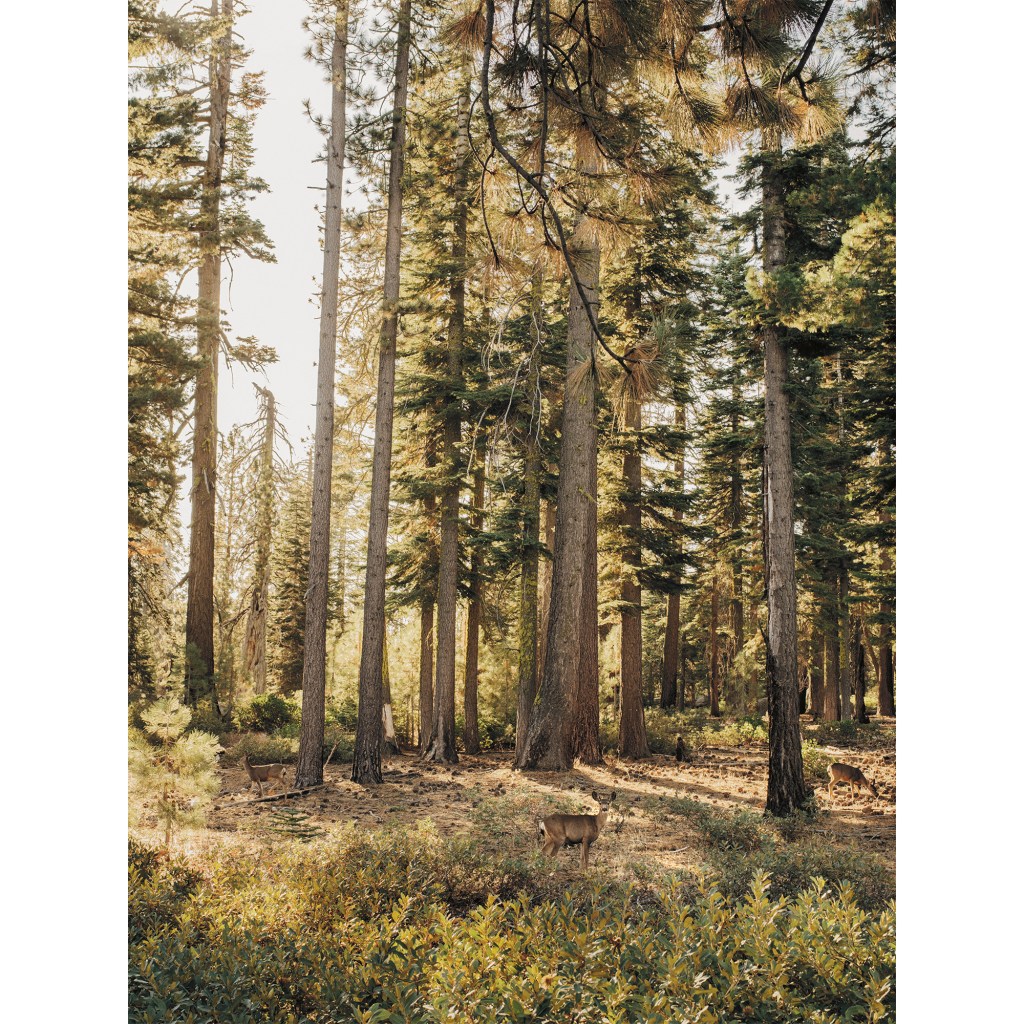

They anticipated the trip would signify an act of healing and self-love, but the group faced challenges from the start, with ash raining down as they ascended the first thousand feet through Jeffrey pine and western juniper. Thirteen days later, Kara Keller (citizen of Bishop Paiute, Nüümü, Lytton Pomo), Amara Keller (Payahuupü Nüümü) and Jaylyn Gough (Diné) joined them. Anna Hohag (Bishop Paiute, Nüümü) would be the last to meet the women five days following, when my group and I would accompany her along Kearsarge Pass to deliver the final resupply.

The women traced the route through granite-pinched canyons and forests so dense they couldn’t tell the time of day. They camped at quiet unnamed lakes and walked slowly, eventually breaking above the tree line, where talus slopes are set beneath massive cirques gouged by glaciers for time immemorial. Occasionally, they’d pause to admire ice-blue lakes on their way out. It’s a trail that’s popular among hikers for a reason.

Amid the big scenery, though, the women confronted bigger reminders of unfreedom. Trail signs etched with labels like “Squaw Lake” evoked derogatory images of Native women, while markers like “Muir Pass” stripped the land of its Indigenous place names. When the group encountered one of these signs, they’d rename the destination, speaking its Indigenous name aloud.

“Our ancestors used the trail to trade, travel and manage the landscape as stewards of the land,” said Anna Hohag, a Paiute attorney from Payahüünadü. “When our people were removed, our places and routes were replaced with outsiders, and our histories and identities erased from the trail.”

The women pitched their tents each night near meadows dotted with late-summer wildflowers like purple monkeyflower and blue lupine. They counted constellations, imagining the ancestors who walked the route before them. Hiking—connecting to one another and the land in this way—proved tiring, but they felt pleased with their progress.

They greeted the darkness with a sense of anticipation. Many of them hiked with aching ankles, bulging blisters and tangled emotions.

The women posted about their progress on social media and, soon enough, hikers began to recognize them on the trail, pausing to ask, “Are you Indigenous Women Hike?” The inquiry surprised them at first, but soon they began to look forward to the impromptu education sessions that followed. They often spent hours alongside other hikers, pausing to share water and snacks, or teach them about the often-overlooked history of the region.

Back on the Nüümü Poyo, I located my childhood friends by the sound of their laughter echoing through the forest near the 170-mile mark close to Bullfrog Lake. We embraced and exchanged stories, our excitement cutting through our exhaustion. Though they’d hiked much farther than our resupply group, the women radiated energy.

I marveled at my friends’ strength early the next morning on my way back to the Kearsarge Pass trailhead. We’d spent long days together as little girls, but now they’d taken to the trail as women. Indigenous Women Hike represented more than a group traveling on a trail together. The journey established our connection to the land and our ancestors. Jolie told me she’d found her place in the world through this experience. But she’d also said, “Indigenous Women Hike isn’t just me. It’s about the work we are doing in our communities.”

On the final day of their journey, Aug. 26, the women woke at 1am to frigid temperatures at 11,493-foot-high Guitar Lake to begin their push to the summit of Tumanguya. They greeted the darkness with a sense of anticipation. Many of them hiked with aching ankles, bulging blisters and tangled emotions. Still, they convened at the top of the tallest mountain in the contiguous U.S. by 10am.

A handful of hours and countless switchbacks later, family, friends, community members and elders surrounded the women as, at long last, they reached the pavement at Whitney Portal. Their loved ones cheered, holding signs with messages like “ohobu huhupi,” or “strong women,” in Nüümü. The group devoured pizza, barbecue and cupcakes—all the things they’d been dreaming about for days.

The road out from the southern terminus of the Nüümü Poyo. The women finally touched down on the pavement at Whitney Portal on Aug. 26, 2018. (Photo Credit: Benjamin Rasmussen)

As the women dropped their packs and kicked off their boots, their minds turned to those who had come before. Our ancestors survived the Gold Rush, the California Genocide, forced assimilation and much more. Their sacrifices allowed this group of women to start something new, hiking more than 200 miles and stepping off the Nüümü Poyo on a warm August day in 2018.

Indigenous Women Hike completed two additional journeys in 2019, one on the Nüümü Poyo and another led by local Quechua women in Peru. Today, the California-based organization hosts a gear library to make experiences like these more accessible to more people, and Jolie frequently speaks about Indigenous rights and public lands in university classes. She hopes to return to the Nüümü Poyo each year to encourage people to connect with each other, honoring themselves and the land in the tradition of our ancestors.

Editor’s note: This article would not have been possible without the information provided by the women mentioned. The Uncommon Path editorial team would like to acknowledge and thank them for the time and energy they devoted to the telling of their story.